SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

RESEARCH ARTICLE

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010

109

black hypertensives in South Africa documented a frequency of

occurrence of 33.5%. Therefore, about a third of newly diagnosed

subjects with hypertension already have at least two other major

cardiovascular risk factors, and are already at increased risk of

developing cardiovascular events. It is also more likely that other

cardiovascular risk factors might appear in these patients over

time.

6,10

Therefore, newly diagnosed subjects with hypertension

should be adequately screened for other cardiovascular risk

factors so as to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease in the

population.

The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among hypertensive

subjects was however lower than that reported among Caucasians.

A report fromSpain shows that 52%of a hypertensive cohort fulfilled

the NCEP ATP III criteria for diagnosing the metabolic syndrome.

19

Some authors have linked race with the frequency of occurence

of the metabolic syndrome and suggested that African blacks are

at a lower risk than whites and Indians.

20

It has been suggested

that black Africans have lower serum levels of lipoproteins and

apolipoproteins than their Caucasian counterparts.

21

Blacks have

also been reported to have a lower blood level of total cholesterol

when compared to whites, and a comparably higher value of HDL

cholesterol, especially among females. This was suggested to be

due to the dietary pattern in blacks, which is particularly low in

dietary fat, especially among Nigerians.

21

This and a possible genetic

difference may be responsible for the difference in frequency of

occurence of cardiovascular risk factor clustering among black and

Caucasian subjects.

10,22

Hypertension has been closely associated with many other

cardiovascular risk factors. This clustering of risk factors increases

the risk of cardiovascular events for these groups of patients.

22-24

The suggested reason for the increased cardiovascular risk

factors among hypertensive subjects is the similar pathogenetic

pathways underlying the clustered risk factors.

25,26

These include

insulin resistance, hyperinsulinaemia, inflammation and the

hyperadrenergic state.

Hypertensive subjects with the metabolic syndrome were

significantly older than their counterparts without the MS. There

were more female than male hypertensives with the metabolic

syndrome. Several studies have documented increased prevalence

with increased age and the female gender.

27-31

However reports

are not consistent, as other reviews have found marginal increases

in prevalence among males.

27

This gender-related difference may

be due to differing work-related activities, and cultural views on

body fat and work-related activities. The apparent increasing

prevalence of the metabolic syndrome may be real, since many of

the components increase in prevalence with age.

Hypertensiveswith themetabolic syndrome seemto be thosewith

a greater degree of target-organ damage, as indicated by increased

prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiomegaly. Left

ventricular hypertrophy is an important pointer to cardiovascular

risk and morbidity. Apart from this, hypertensive subjects with the

metabolic syndrome also had a higher QTc, body mass index and

systolic blood pressure than those without the metabolic syndrome.

QTc prolongation is a non-invasive marker for the development of

arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.

The combination of hypertension, obesity and low HDL-C was

the commonest pattern among hypertensive subjects with the

metabolic syndrome, followed by the combination of hypertension,

obesity and impaired fasting plasma glucose. Hypertensives with

the metabolic syndrome had higher fasting plasma glucose levels

than those without the metabolic syndrome. Impaired fasting

plasma glucose has been associated with an increased likelihood of

developing diabetes mellitus. These groups of hypertensive subjects

therefore require intensive cardiovascular evaluation and care to

reverse the increased tendency for the development of diabetes

and cardiovascular diseases.

As Africa undergoes an epidemiological transition, the

inevitable increase in prevalence of the metabolic syndrome would

have important implications with respect to the potential rise in

the incidence of ischaemic heart disease and diabetes. Available

evidence suggests that the prevalence of cardiovascular disease

among Nigerians is increasing.

32-34

Therefore it is important to

identify high-risk individuals for target therapy to reduce the overall

prevalence of cardiovascular disease.

Conclusion

This study showed that the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome

among newly diagnosed hypertensive Nigerian subjects was high

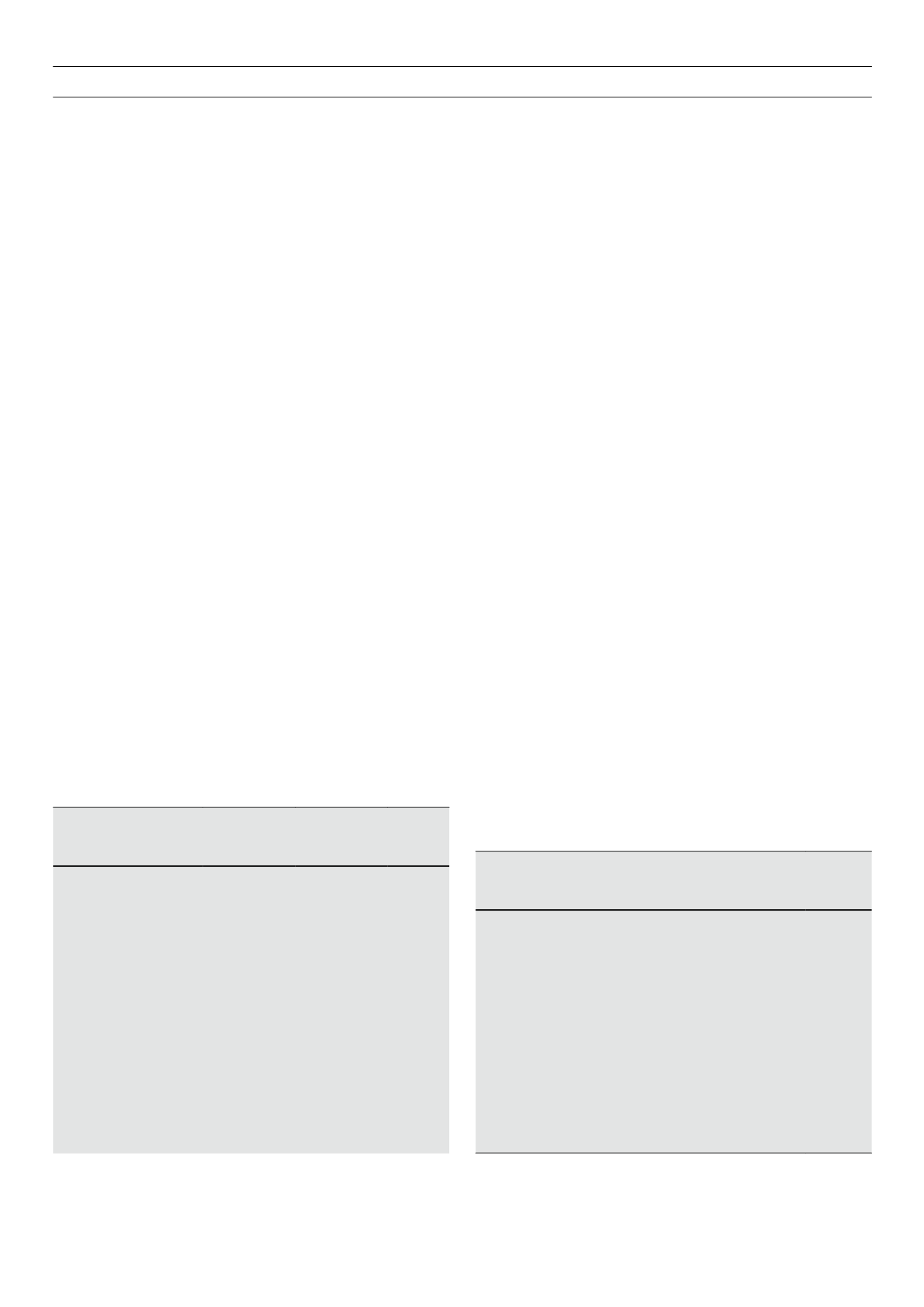

Table 4.

Pattern of combination of risk factors among subjects with the

metabolic syndrome

Combination of risk factors

Number

(%)

Hypertension

+

obesity

+

low HDL

29 (20.7)

Hypertension

+

obesity

+

IFG

5 (3.6)

Hypertension

+

obesity

+

hypertriglyceridaemia

3 (2.1)

Hypertension

+

low HDL

+

hypertriglyceridaemia

2 (1.4)

Hypertension

+

low HDL

+

IFG

2 (1.4)

Hypertension

+

hypertriglyceridaemia

+

IFG

1 (0.7)

Hypertension

+

hypertriglyceridaemia

+

IFG

1 (0.7)

Hypertension

+

obesity

+

low HDL

+

hypertriglyceridaemia

+

IFG 1 (0.7)

HDL: high-density lipoprotein, IFG: impaired fasting glucose.

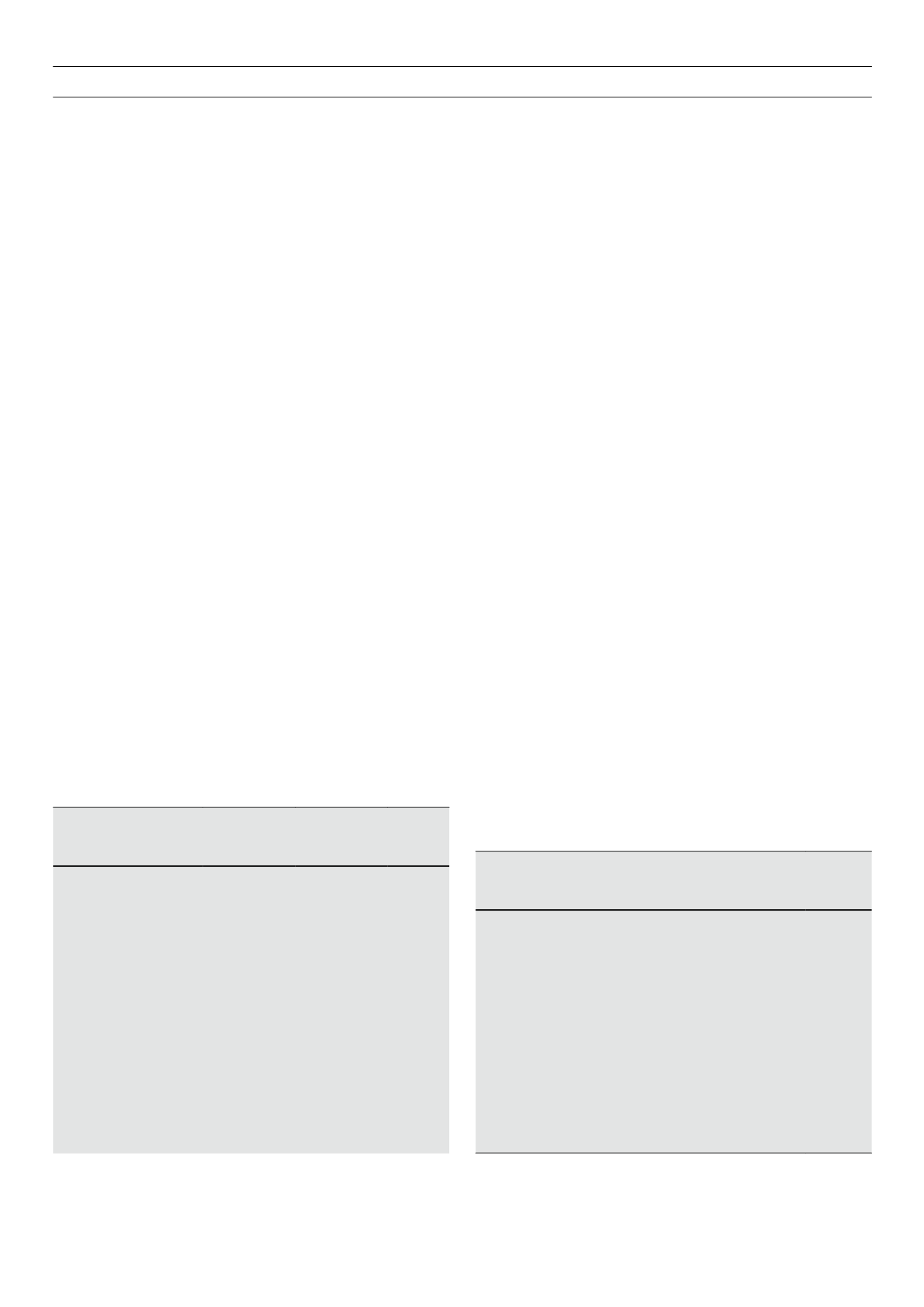

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of hypertensive subjects with and without

the metabolic syndrome

Parameter

Hypertensives

with MS

(

n

=

44)

Hypertensives

without MS

(

n

=

96)

p

-value

Age (years)

57.22

±

9.65 53.52

±

10.58

<

0.05*

Gender

38 (27.1%)

39 (27.9%)

<

0.05*

Mean BMI (kg/m

2

)

30.15

±

5.27 24.14

±

4.10

<

0.005*

Mean SBP (mmHg)

141.36

±

23.66 130.16

±

29.50

<

0.05*

Mean DBP (mmHg)

86.17

±

18.19 80.97

±

17.54

>

0.05

Hypertensives with LVH

39 (70.9%)

56 (65.9%)

<

0.05*

Mean QTc (msec)

0.42

±

0.03

0.41

±

0.03

<

0.05*

FBS (mmol/l)

4.7

±

1.6

5.6

±

1.2

<

0.05*

BMI: body mass index, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood

pressure, LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy.

*Statistically significant.