REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

14

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 1 • MARCH 2010

>

3.5 mg/mmol in women.

This definition takes no account of age. It is well recognised

that GFR declines with age and there is concern among some

nephrologists that a disproportionate number of elderly

people will now be inappropriately diagnosed and managed

as having CKD when their renal function is, in fact, normal

for their age.

NICE aims to minimise this risk by restricting testing for

CKD to individuals with certain known risk factors and by

specifically stating that age itself should not be seen as a risk

marker. Nonetheless, a high proportion of patients diagnosed

with CKD, or at least a finding of reduced eGFR, are elderly

and it is currently unknown whether or not these individuals

will benefit from management.

Compared to eGFR, the case for proteinuria as a marker

of systemic vascular disease, and thus a good basis for

management to reduce vascular risk, is more compelling.

The kidneys are highly vascular organs taking 25% of cardiac

output and each containing about one million glomeruli,

which are essentially knots of blood vessels. Leakage of

protein from blood vessels, such as retinal exudates in

hypertension or diabetes, has long been recognised as a

marker of systemic vascular disease and the presence of

protein in the urine is another manifestation of the same

systemic process. Proteinuria is

prima facie

evidence of harm

and thus is a strong basis for treatment, even in the elderly.

Which test should be adopted to test for proteinuria

in at-risk individuals?

ACR is the most sensitive test for proteinuria. Dipsticks are

cheap and convenient, and will detect proteinuria when

the ACR is around 45 mg/mmol. To identify individuals

with proteinuria below this level is known to be important

in people with diabetes, but there is no basis on which to

extrapolate this benefit to those without diabetes.

NICE guidance states that an ACR

<

30 mg/mmol need not

prompt a change in management in non-diabetic individuals.

So can the additional expense of ACR over dipstick be justified

in non-diabetic patients? This is a debate that is currently

unresolved. Meanwhile, testing for ACR in all patients on a

CKD register has been introduced as a performance indicator

in the 2009 Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF).

Practicalities of testing for CKD

NICE guidance states that testing for CKD should be offered

to patients with the following risk factors:

hypertension

•

cardiovascular disease

•

renal stone disease or prostatic problems

•

known multisystem disease with potential for renal

•

involvement

family history of CKD

•

incidental finding of haematuria or proteinuria.

•

Even though it is stated in NICE guidance that advanced

age should not be considered a risk factor, there is a high

proportion of the elderly population in these at-risk groups.

Practitioners are therefore encouraged to take account

of age and co-morbidity (and thus likely prognosis) before

incorporating the elderly into management programmes. No

clear guidance can be given on this matter: it is a distillation

of common sense, experience and good clinical judgement.

However, a competent medical evaluation is required rather

than a protocol-driven pathway.

eGFR estimations can fluctuate, particularly when eGFR

is just below the normal range (eGFR 45–60 ml/min). It is

therefore important to minimise these fluctuations by asking

patients to abstain from meat for 12 hours before collecting

a urine sample and to maintain hydration with clear fluids.

Patients attending for fasting blood tests often think they

should take ‘nil by mouth’ and so are tested when relatively

dehydrated.

The initial screen for proteinuria does not require an early

morning sample. However, if initial ACR is 30–70 mg/mmol,

a repeat test using an early morning sample is advised as

minor proteinuria may be increased into the abnormal range

by exercise and orthostasis. If the initial sample shows ACR >

70 mg/mmol, this is likely to represent significant proteinuria

requiring intervention. Proteinuria is also increased in the

presence of hypertension and one might expect the ACR to

fall once blood pressure has been brought under control.

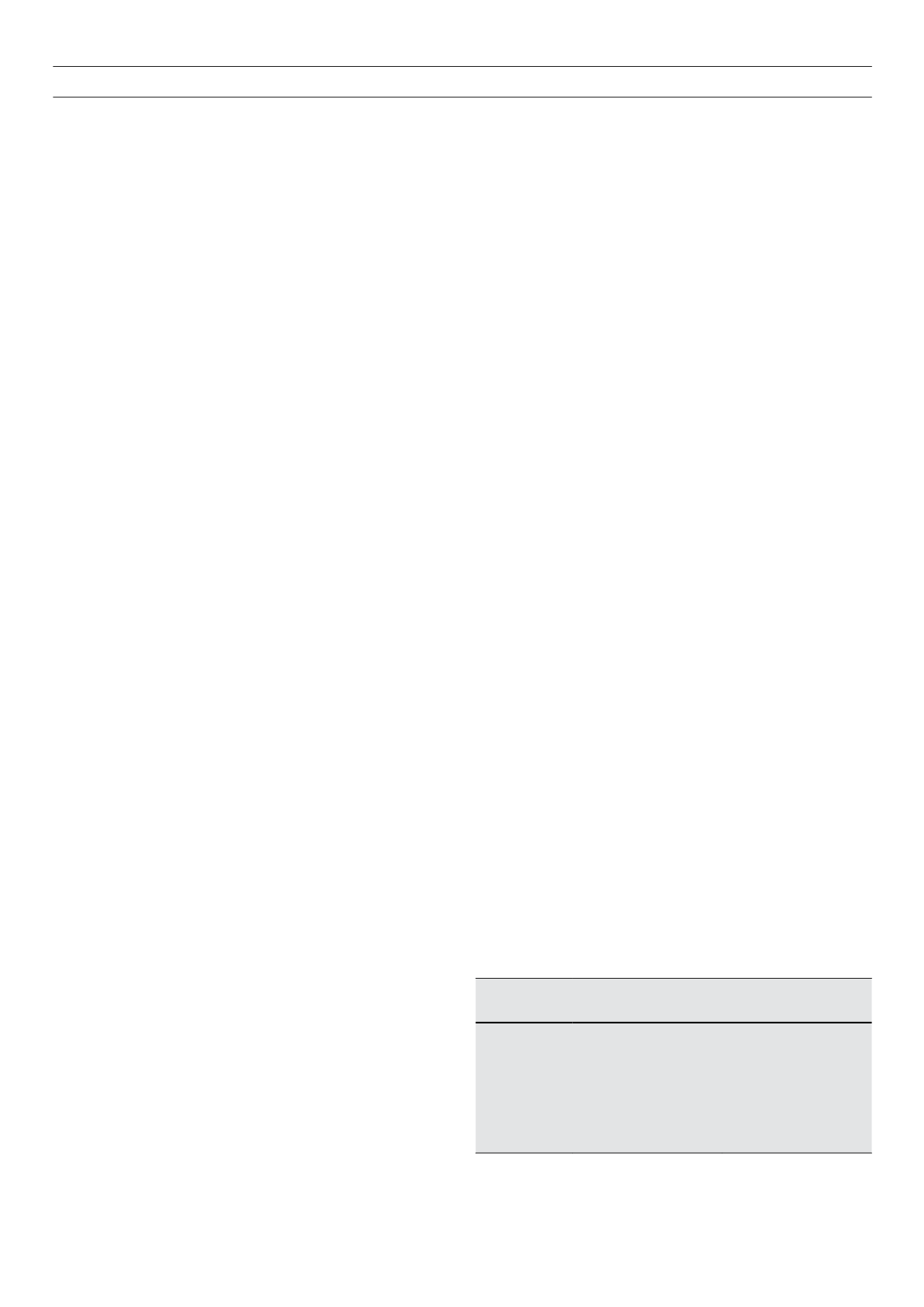

Monitoring CKD

The testing frequency recommended by NICE is outlined in

Table 2. Most individuals with stage 4–5 CKD will be under

the care of the specialist renal service. However, elderly

patients with eGFR

<

29 ml/min are frequently identified

who have very stable eGFRs and show no trajectory towards

end-stage renal failure. These might opt to be monitored as

outlined in Table 2 in a primary care setting, with referral

should their function be seen to decline.

ThemainpurposeofmonitoringCKDistoidentifyindividuals

with progressive CKD, who are at risk of developing end-

stage kidney disease within their expected natural lifetime. It

is important to realise that even with optimal management,

CKD is a progressive disease. Management may slow decline

but failure to halt progression does not necessarily mean that

treatment has been sub-optimal or ineffective.

NICE defines progressive CKD as a decline in eGFR of

>

5ml/

min/1.73 m

2

in one year (or 10 ml/min/1.73 m

2

in five years).

Table 2.

Stages of CKD and frequency of eGFR testing

CKD stage

eGFR (ml/min)

Frequency of monitoring

1 and 2

>

60

Annually

3A and 3B

30–59

6-monthly

4

15–29

3-monthly

5

<

15

4–6-weekly

CKD

=

chronic kidney disease; eGFR

=

estimated glomerular filtration rate