VOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 • NOVEMBER 2018

81

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

PASCAR ROADMAP

and the draft.

15

Comments were received and the draft was

amended.

The task force reviewed the final draft of the roadmap in Mexico

in June 2016, which was then submitted for external peer-review by

three independent experts in hypertension and policy development.

The subsequent review was done by a group of experts in

cardiology, nephrology, primary care and research (including clinical

trials). Comments were reviewed and discussed by the panel and

incorporated into a revised and final document.

PASCAR searches and surveys on the status of hypertension

policy programmes and clinical practice guidelines

From May to July 2015, an internal PASCAR survey was conducted,

aiming to determine which African countries ran hypertension

control programmes focusing on policy. Using the Survey Monkey

software tool,

16

national hypertension experts from 40 countries

were asked whether a hypertension policy programme was

operating in their country and could be judged as being ‘dormant’,

‘not much active’, ‘active’, or ‘very much active’.

Among the responders (

n

= 127) representing 27 SSA countries,

we noticed that up to 63.7% did not have a hypertension policy

programme or that it was dormant or not very active. This

regrettable situation highlights the importance of a continental

initiative to develop a hypertension policy to address BP control

from a population-wide and high-risk approach.

Evidence has shown that explicit clinical practice guidelines

(CPGs) do improve the care gap by providing practitioners and

health-service users with synthesised quality evidence regarding

decision-making.

17

In another PASCAR study, we assessed the

existence, development and use of national guidelines for the

detection and management of hypertension in the African region,

regardless of quality.

Between May and July 2015, CPGs for hypertension were

searched, using a scientifically developed search strategy. Searches

were done using Google and PubMed. Search terms included

(country name) AND (hypertension OR HTN OR high blood pressure)

AND (clinical practice guidelines OR treatment guide). French,

Portuguese and Spanish translations were included in the search

strategy.

Websites of ministries of health, national medical associations

and the WHO were hand-searched, authors were e-mailed, and

requests were sent on Afronets to obtain copies of CPGs for

hypertension. To be included in the search, the CPGs had to be

available and provided in full-text versions for assessment by the

review team, comprising three independent authors. CPGs from

Europe or South America or those that could not be obtained were

considered non-existent. Two national hypertension experts were

contacted for confirmation on countries for which we could not find

CPGs on hypertension. CPGs published in peerreviewed journals

needed to be readily accessed by end-users. E-mail messages were

used for further clarification.

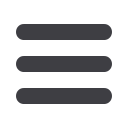

In Fig. 4, the 2015 map is presented of countries with clear

evidence of the existence of national guidelines for detection

and management of BP across Africa. Only 16 (25.8%) out of 62

countries had CPGs complying with our search criteria. No evidence

of CPGs on hypertension management could be found for the other

46 (74.2%) countries. Given that the only existing multinational

expert recommendations for the management of hypertension

in Africa dates back to 2003 and has not been updated since,

18

we concluded that there is a legitimate, pressing need to support

African ministries of health with a clear hypertension roadmap.

PASCAR roadmap to decrease the burden of hypertension

in Africa

To reduce the incidence of CVD through treating hypertension

in the African region, it will be necessary to increase the rates of

detection, treatment and control of the disease. The 10 actions that

need to be undertaken by African ministries of health to achieve a

25% control of hypertension in Africa by 2025 (Fig. 4) are listed

below and we include an explanation as to why (bullets) and how

(dashes) this needs to be done.

1. All NCD national programmes should additionally contain a

plan for the detection of hypertension.

• The hypertension crisis has yet to receive an appropriate

response in SSA.

19

• Incidence of hypertension increased by 67% since 1990 and

was estimated to cause more than 500 000 deaths and 10

million years of life lost in 2010 in SSA.

20,21

• Hypertension is the main cause of stroke, heart failure and

renal disease in SSA.

• Stroke, which is a major complication of uncontrolled hyper-

tension, has increased to 46% since 1990 and essentially

affects breadwinners.

20

• Failure to control hypertension and its economic repercussions

through revising health policies and services endangers the

economic prosperity of all African nations.

22

– All SSA countries should have adopted and should follow

the WHO global agenda of reducing NCDs by 2020.

– When reporting to the Ministry of Health and the WHO,

stakeholders should report specifically on hypertension.

– National cardiac and hypertension societies should

monitor the prevalence, awareness and control rates of

hypertension and report to PASCAR.

– Government, private sector, academia and community

Fig. 4.

2015 map of African countries with evidence of existing clinical

practice guidelines for hypertension management and 10 actions to reduce the

hypertension burden in Africa