REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

56

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 2 • JUNE 2010

Atrial fibrillation: which patients should be managed in

primary, secondary and tertiary care?

David Jones, tom wong, diana gorog, vias markides

Definition

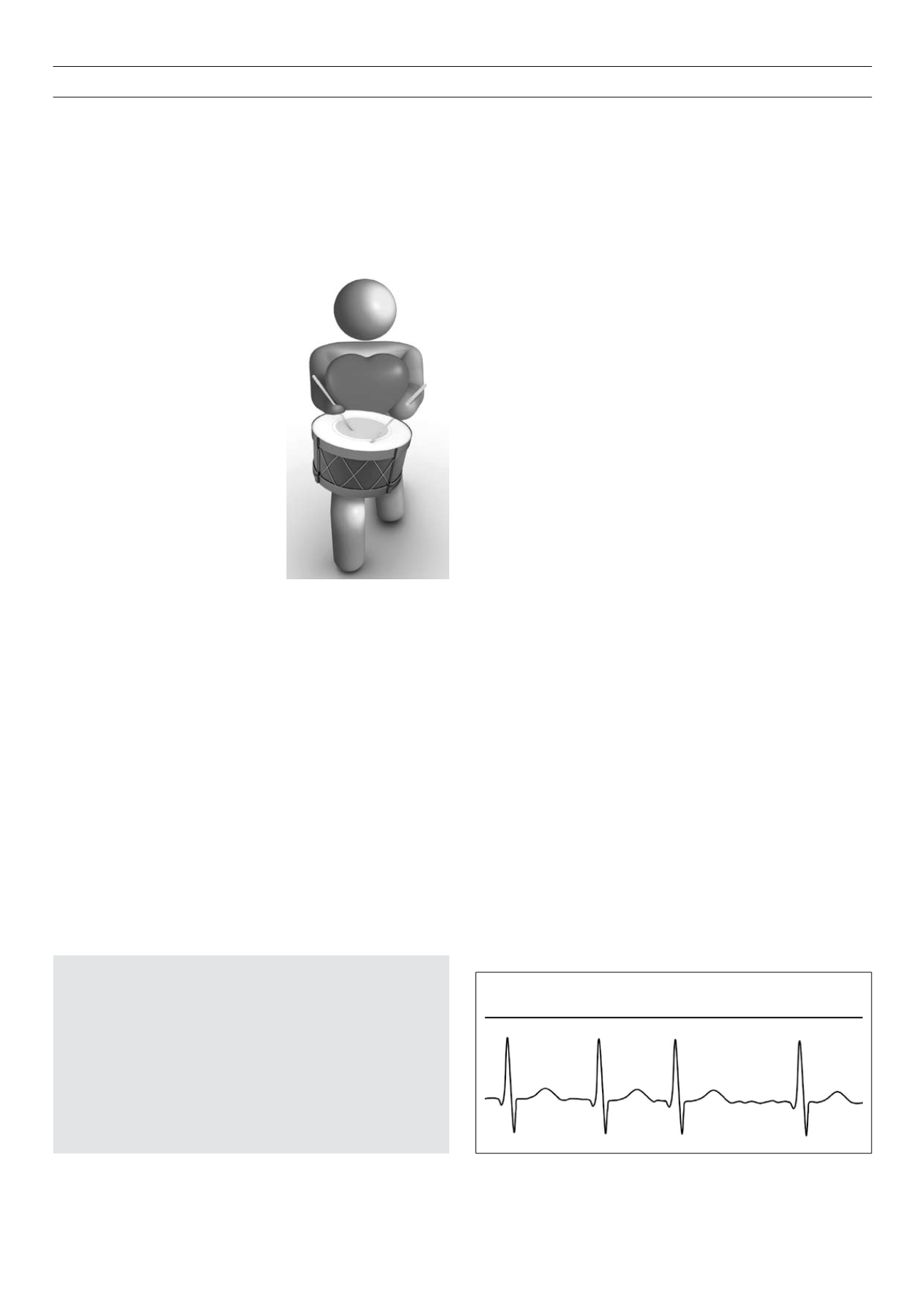

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is defined electrocardiographically as the

loss of distinct P waves

on the surface ECG accompanied by an

irregularly irregular

ventricular (QRS) response (see Fig. 1). Low

amplitude, extremely rapid and irregular (in rate and morphology)

atrial

activity may be discernible as ‘f ‘ waves. AF is usually, but not

always, associated with inappropriately rapid heart rates. It can also

be associated with significant bradycardia during sinus rhythm, and

with tachycardia during paroxysms of atrial fibrillation

(tachy-brady

syndrome)

.

Epidemiology

AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, affecting

1–2% of the general population.

1,2

Recent studies indicate that the

lifetime risk may exceed 20%.

3

Prevalence increases with age, rising

to 8% in people over 80 years,

4

over two-thirds of individuals with

AF are aged 65–85.

5

It is estimated that there are 2.3 million people

in the United States, and 4.5 million in the European Union with

AF.

2

The prevalence is increasing – in part due to population ageing,

but also due to an increase in age-adjusted AF incidence – which

clearly has significant implications for health service planning.

AF is associated with increased mortality. In the Framingham

Study, AF conferred a relative all-cause mortality risk of 1.8.

6

Much

of this is attributable to stroke, the risk of which is increased five-

fold in those with AF – but which varies according to age and

comorbidities.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

AF is associated with several conditions, including hypertension,

heart failure and valvular heart disease, thyrotoxicosis, and

obesity.

7

Many of these conditions can cause mechanical changes

(including stretch and fibrosis) and electrical changes (remodelling)

that, when coupled with a genetic predisposition

8

and ectopic

triggers during favourable autonomic activity, can precipitate AF.

AF in itself enhances further remodelling, so encouraging its own

perpetuation.

9

The pathogenesis of AF involves a complex interplay between

mechanisms of initiation (

eg

extremely rapid electrical activity

A

trial fibrillation is the

commonest sustained

cardiac arrhythmia, and

has a significant impact on

morbidity and mortality. It is

a leading cause of stroke, and

suitable

thromboprophylaxis

should be considered in all

patients. Treatment is tailored

to the individual. This article

will review the management

strategies for patients with

atrial fibrillation, and discuss

the roles of primary, secondary,

and tertiary care.

In

Circulation of the Blood

(1628),

William Harvey commented that:

“It is … evident that the auricles pulsate, contract … and

eject the blood into the ventricles. [The auricle] has to help

infuse blood into the ventricle so that … [the ventricle] …

may send it on with greater vigour.”

This ‘primer pump’ function of the atria contributes about 10–20%

towards ventricular filling and, although not vital for normal

resting heart function, plays an increasing role in disease and in

maximising cardiac output during exercise. This function is lost in

atrial fibrillation (AF), when the atria undergo rapid and chaotic

excitation, discharging at 300–600 beats per minute.

In a normally functioning heart, the only electrical communication

to the ventricles is through the atrioventricular (AV) node, whose

electrical properties cause blockage of many of these impulses, so

protecting the ventricles from life-threatening rapidity. However,

during AF the ventricles are subjected to higher rates of excitation

than normal, particularly during exercise, and beat-to-beat variability

leads to an irregular pulse and suboptimal haemodynamics.

Furthermore, the loss of atrial contraction encourages thrombus

formation and can lead to the most feared complication of AF,

embolic stroke.

Correspondence to: David Jones

Fellow in Cardiac Electrophysiology, Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS

Foundation Trust and Imperial College London.

e-mail:

Tom Wong, consultant cardiologist, Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS

Foundation Trust and Imperial College London

Diana Gorog, consultant cardiologist, East & North Hertfordshire NHS Trust

and Imperial College London

Vias Markides, consultant cardiologist, Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS

Foundation Trust and Imperial College London

S Afr J Diabetes Vasc Dis

2010;

7

: 56–63.

doi: 10.3132/pccj.2010.001

Figure 1.

ECG in atrial fibrillation.