DRUG TRENDS

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

38

VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 • MARCH 2011

Dr Kramer said.

The search for a common aetiology for the

metabolic syndrome was first grounded in

insulin resistance but this unifying aetiology

has remained unproven. Subsequently, visceral

obesity, inflammation and hyper-insulinaemia

were explored as a common aetiology, but

these attempts also failed. So there was no

real advantage in calling these conditions the

metabolic syndrome’, Dr Kramer explained.

At the practical level of general practitioner

and patient communication, the cluster of dys-

glycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in

the presence of visceral obesity may perhaps

usefully be described as ‘the syndrome that

was once known as the metabolic syndrome’,

Dr Larry Distiller added.

The changing gut microbiome: is it

killing us?

In a journey to look at childhood obesity differ-

ently and in the context of the increase in both

type 1 and type 2 diabetes, Dr David Segal,

paediatric endocrinologist with academic com-

mitments at Wits University Medical Faculty

and also in private practice at CDE, Parktown,

explored the available medical literature and

interpreted new data to provide concepts for

clinical intervention.

He targeted two main features of modern

obesity: firstly, neuro-economics (the cost–ben-

efit of obtaining food), and secondly, the con-

sequences of increased fat and carbohydrate

intake, which are challenging the

β

-cell and

altering the gut microbiota so that food transi-

tion and absorption is modified. ‘While genetic

studies have added to our knowledge of the

gene control of appetite, satiety and feedback

mechanisms, they have failed to give us a prac-

tical option to control obesity’, he said.

The field of neuro-economics applied

to food calculates the price-cost in energy

expended, and the risk and effort to procure

the food that we eat, and relates it to demand,

which is ever present as appetite, and supply,

which in urban areas is plentiful at the nearest

supermarket.

‘In neuro-economic terms, our food is very

cheap and is extra-ordinarily palatable, thereby

stimulating excess demand. This demand

will remain consistently high unless we can

increase the energy-risk cost or reduce the pal-

atability’.

1

‘In effect, this means that we cannot

control obesity in our modern urban setting’,

Dr Segal pointed out.

In a study on the burden of diabetes among

American youth, the SEARCH study

2

has

shown the rising prevalence of type 2 diabe-

tes in different racial groups in six states in the

USA. Among younger children from birth to

nine years of age, type 1 diabetes accounted

for approximately 80% of diabetes cases,

while among the older group (10–19 years)

type 2 diabetes ranged from 6% in the non-

Hispanic whites, to 76% (1.74% per 1 000

cases) among American Indians.

Interestingly, the only group in the 15- to

19-year-olds to show the same prevalence

(3/1 000) for both type 1 and type 2 diabetes

was the African-American female population.

‘Type 2 diabetes in adolescents is associated

with increased obesity, with a five-year lead

time between obesity

occurrence (BMI

≥

30

kg/m

2

) and the devel-

opment of diabetes’,

Dr Segal noted.

In evaluation of

the rising trend of

childhood type 1

diabetes, there is an

association with rising

childhood

obesity.

Up until the 1950s,

diabetes was seen

as a single disorder

with an aggressive

presentation in the

young. ‘In the 1960s,

scientific

evidence

saw the emergence

of an auto-immune

basis for type 1 dia-

betes with lympho-

cytic infiltration of the

islets, a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) link to

diabetes and islet antibodies. We do not have

a clue as to what triggers the immune system

to attack the

b

-cell’, Dr Segal said.

An hypothesis that is gaining credence is

the ‘accelerator’ hypothesis which proposes

that weight and associated insulin resistance

accelerate loss of

b

-cells in both type 1 and

type 2 diabetes and the only thing that distin-

guishes these two forms of diabetes is the rate

of progression. There is considerable evidence

that weight gain in early life can be used to

predict at two years of age the risk of islet

immunity in children with first-degree relatives

with type 1 diabetes.

3

Also, over the past 20

years, there has been a steady increase in BMIs

in girls and boys at the time of diagnosis of

their type 1 diabetes.

4

‘If we look at HLA risk markers for diabetes,

it is evident that there are genotypes that are

related to the development of type 1 diabetes,

1.5 latent autoimmune diabetes in adulthood

(LADA) and type 2 diabetes’, Dr Segal said.

Because of environmental pressures, a lower

predisposing genetic component is needed

today to result in the development of diabe-

tes than was required in the 1930s. ‘The pre-

disposing reactive genotype leads in fact to a

faster tempo of

b

-cell loss in the presence of

increasing insulin resistance’, Dr Segal pointed

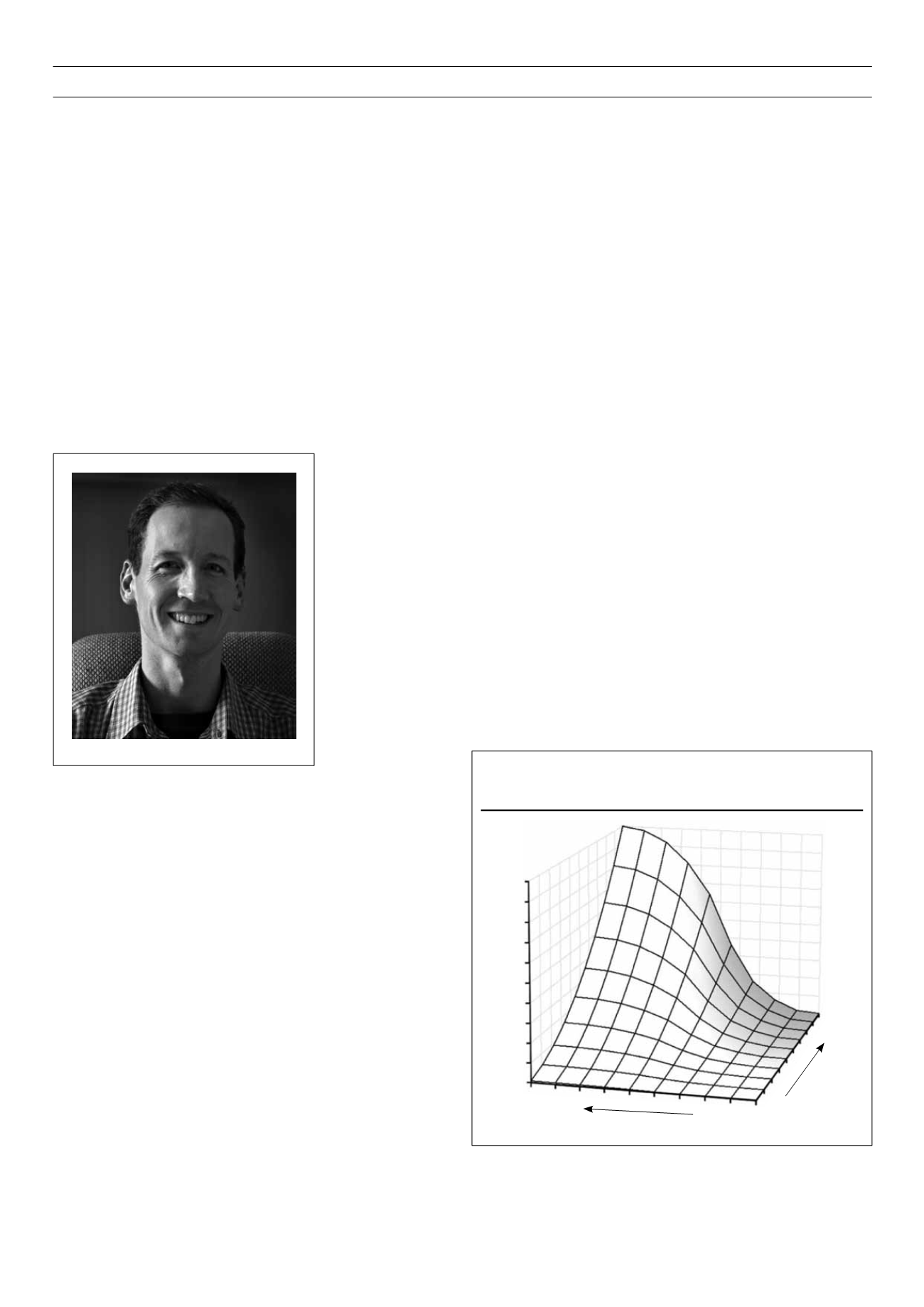

out (Fig. 1).

In adolescents, it is the ongoing weight gain

that predicts the development of type 2 diabe-

tes rather than glucose levels, insulin resistance

Dr David Segal

Figure 1.

Relationship between the accelerator genotype, insulin resistance

and the probability of diabetes.

Probability of diabetes

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

Insulin resistance

Accelerator genotype