VOLUME 13 NUMBER 1 • JULY 2016

9

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

RESEARCH ARTICLE

problematic to understand for some patients: ‘feeling constantly

burned out by constant effort to manage diabetes’ and ‘not having

a clear and concrete goal for managing diabetes care’.

Some adolescents and adults had challenges with specific words

in the items although they were able to deduce the meaning of

the entire question. The words and concepts that the patients

found challenging were ‘overwhelmed’, ‘regimens’, ‘unsatisfied’,

‘burnout’, ‘physicians’ and ‘concrete goal’. The patients were also

able to suggest some replacements to the words they initially had

challenges with to include ‘treatment plan’ for ‘regimens’, ‘unhappy’

or ‘happy’ for ‘unsatisfied’, ‘doctor’ for ‘physicians’. In some cases

it was difficult to recall occurrences of certain events evoked by the

questions such as when patients were angry, guilty or anxious and

uncomfortable. These challenges were mostly noted among young

people. Table 8 outlines common problems that were identified, as

indicated above.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the latent structure, reliability

and validity of the PAID among individuals with type 1 or 2 diabetes

in Zambia. The results of our study strongly support a one-factor

solution of the Zambian translation of the PAID, although four items

‘concerned with complications’, ‘feelings of deprivation regarding

food’, ‘coping with complications’ and ‘feeling overwhelmed by

diabetes’ had factor loadings less than 0.30. These low loadings

may result from the fact that all our subjects were out-patients

without any serious complications. It remains unclear why the item

‘concerned about food’ had a low loading considering that initial

interviews by the first author with the patients showed that it was

a major concern.

17

Our data rejected the two-factor model found in Iceland by

Sigurdardottir and Benediktsson,

6

the three-factor model found in

Sweden by Amsberg and colleagues,

7

and the four-factor model

found in the USA/the Netherlands.

18,19

A one-factor model was also

found in the USA/the Netherlands.

18

Originally, the PAID was conceptualised as a unidimensional

scale;

2

therefore, our one-factor structure using all 20 items

remains plausible. Moreover, in studies among Chinese,

20

Dutch

and USA

18

individuals with diabetes, the one-factor solution was

also supported. The Zambian translation of the PAID showed high

internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha and lambda, which has

recently been recommended in the literature because it shows the

least amount of bias.

36

Consequently, a total of at least 16 items

from the EFA results seems useful for clinical assessment to detect

diabetes-related distress and suggest psychological help to Zambian

patients with such distress, with possibly some word changes, as

suggested by the cognitive interview study.

Our study also found that most patients endorsed, ‘worrying

about low blood sugar reactions’, ‘feeling that diabetes is taking up

too much mental and physical energy’, ‘feeling guilty/anxious when

you get off track with your diabetes management’, ‘worrying about

future and possible serious complications’ and ‘feeling depressed

when you think about living with diabetes’ as the most bothersome

diabetes-specific problems, which is consistent with findings by

Sigurdardottir and Benediktsson.

6

‘Worrying about the future and

possible complications’, and ‘feeling guilty when you get off track

with your diabetes management’ were also found to be the most

commonly endorsed by Snoek and associates.

18

It was not surprising that our patients endorsed these items,

considering that the mean score for fear for hypoglycaemic episode

was relatively high (58 ± 12) and the diabetes self-care score was

below average (48 ± 9). Moreover, having a hypoglycaemic episode

in Zambia might be more stressful, as medical care is less available,

compared to Europe or the USA. Furthermore, all the participants

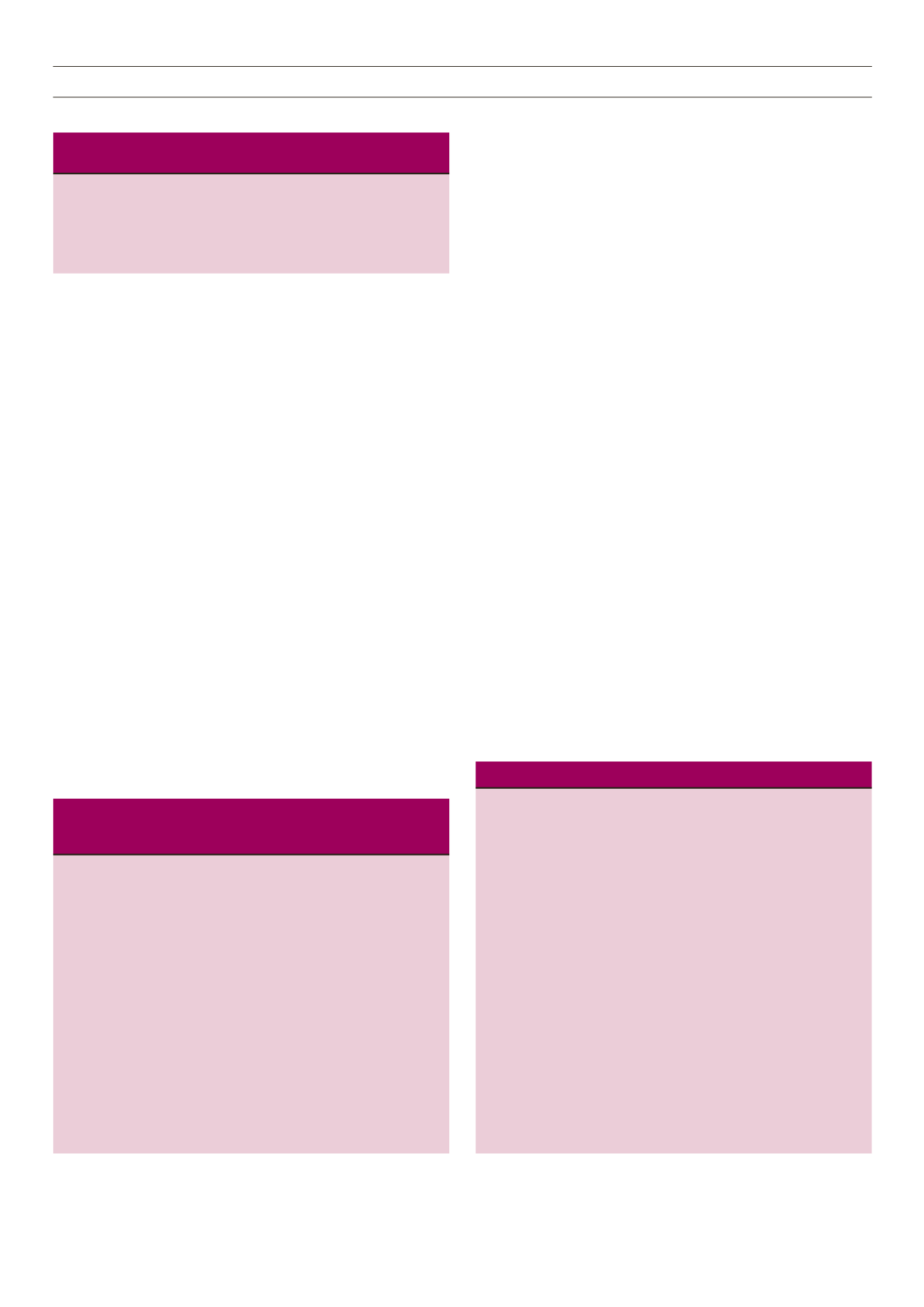

Table 6.

Stepwise multiple regression analyses predicting PAID by

demographic and clinical characteristics in 157 patients with T1DM and

T2DM

Models

Beta

t

p

-value

Model 1: demographic characteristics

Age

0.122

1.286

ns

Being T2DM

0.029

0.313

ns

Being female

0.011

0.138

ns

Socio-economic status

0.005

0.054

ns

R

2

= 0.020

Adj

R

2

= –0.007

p

≥ 0.005

Model 2: clinical characteristics

Body mass index

–0.107 –1.348

ns

Depression (MDI)

0.268

3.122

***

Fear for hypoglycaemia

0.289

3.456

***

Diabetes self-care

0.252

3.249

***

R

2

= 0.335

Adj

R

2

= 0.315

p

≤ 0.001***

*

p

< 0.05, **

p

< 0.01, ***

p

< 0.001.

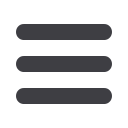

Table 7.

Cognitive interview questions

Warm up question/instruction clarity

Tell me what this introduction is telling you?

Comprehension (question intent and meaning of term)

Can you tell me in your own words what this question was asking?

What does the [word/term] mean to you as it has been used in this question?

Tell me what you were thinking when I asked about [topic]?

Assumption

How well does this question apply to you?

Can you tell me more about that?

Knowledge/memory

How much would you say you know about [topic]?

How much though would you say you have given to this?

How easy or difficult is it to remember [event]?

You said [answer]. How sure are you about that?

How did you come up with that answer?

Sensitivity/social desirability

Is it ok to talk about this diabetes problem area or is it uncomfortable?

The question uses the [word/term]. Does that sound ok or would you choose

something different?

Specific and general probes

Why do you think that [topic] is the most serious diabetes problem?

How did you arrive at that answer?

Was it easy or hard to answer?

I noticed that you hesitated. Tell me what you were thinking?

Table 5.

Correlations between the total PAID, the four PAID factors

(based on previous research) and other variables of interest

Diabetes

Fear for

self-care hypoglycaemia Age SES

¶

BMI

MDI

#

PAID total

0.30**

0.35**

0.12 0.00 –0.14 0.39**

**

p

≤ 0.01, *

p

≤ 0.05;

¶

Socio-economic status;

#

Major depression inventory

total score.