6

VOLUME 13 NUMBER 1 • JULY 2016

RESEARCH ARTICLE

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

(i.e. for PAID total alpha and alpha for each subscale). Values

above 0.70 are regarded as satisfactory.

32

Concurrent validity was

assessed using Pearson’s correlation between PAID total score

and other psychosocial variables of interest. In addition, item

total correlation was computed to evaluate the degree to which

differences among patients’ responses to the items were consistent

differences in their total PAID scores. Correlations among measures

of the same attribute should be between 0.40 and 0.80.

7

A lower

correlation indicates either an unacceptably low reliability of one

of the measures, or that the measures are measuring different

phenomena.

33

Discriminant validity was examined by conducting

a multiple regression analysis to determine the extent to which

PAID scores were predicted by body mass index, depression, fear

of hypoglycaemia and diabetes self-care, after adjusting for age,

diabetes type, gender and socio-economic status.

Results

The lowest PAID item missing value accounted for 1.3% and the

highest item accounted for 3.8%. In particular, five items had the

largest missing value percentages; ‘feeling constantly burned out

by constant effort to manage diabetes’ (3.8%), ‘feeling constantly

concerned with food’ (3.8%), ‘feeling diabetes is taking up too

much of your mental and physical energy’ (2.5%), ‘not accepting

diabetes’ (2.5%) and ‘feeling overwhelmed by your diabetes

regimens’ (2.5%). These items accounted for 15.1% missing

values. The Bartlett test of sphericity was highly significant [

χ

2

(190)

= 1005.533,

p

< 0.001]. The KMO value was 0.86. These statistics

suggest that the EFA can be adequately applied.

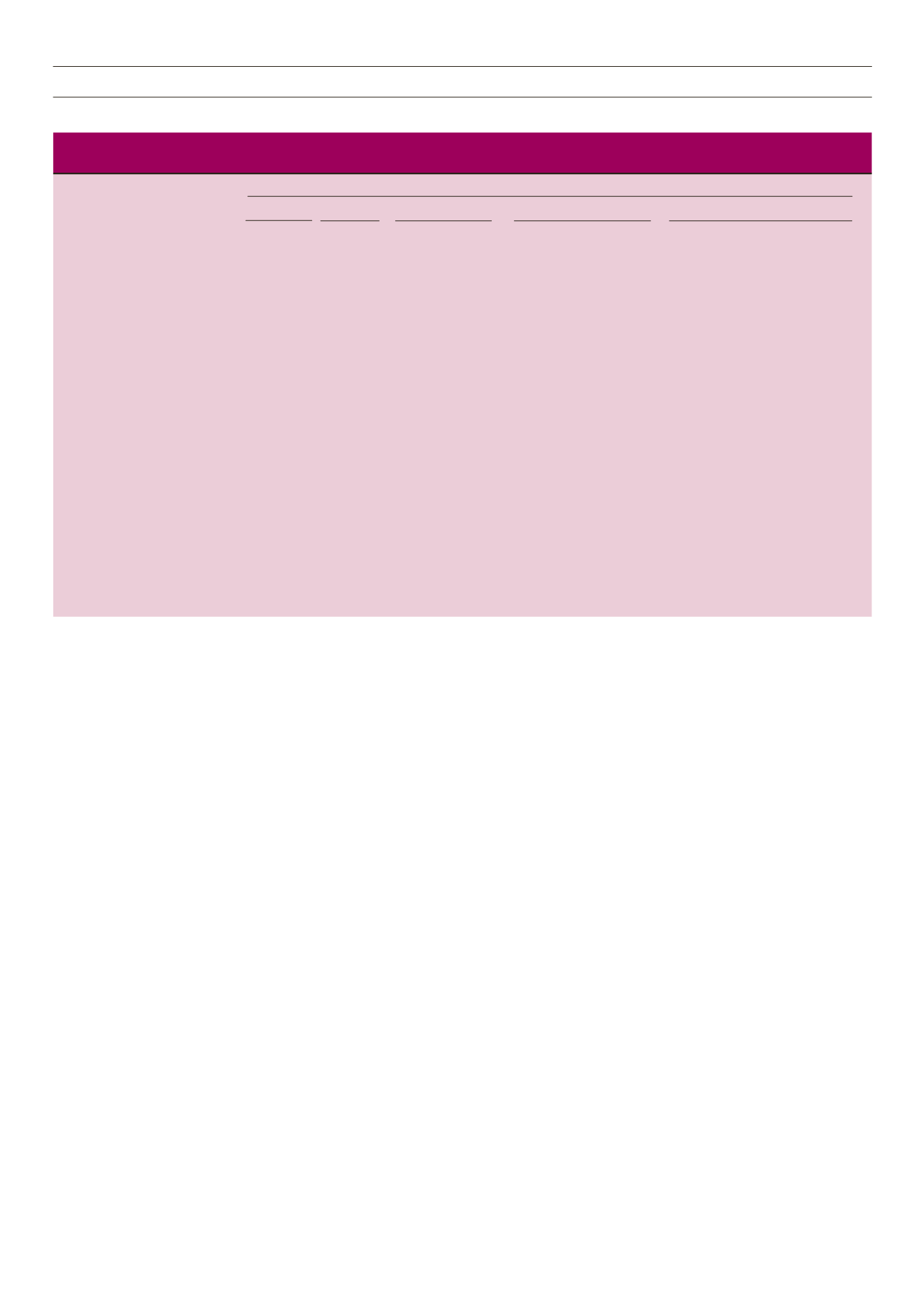

In the second step, principal component analysis using direct

oblimin was conducted and inspection of the Eigenvalues yielded

a maximum of five factors: 6.69, 2.14, 1.35, 1.14 and 1.02 (values

before rotation). Given the ambiguity as to the number of factors

reported in the literature, we explored solutions with different

numbers of factors, working back from five factors. The five-factor

solution could not be used, as many items loaded on more than

one factor and some of the factors could not be interpreted

Consistent with Snoek and colleagues,

18

a forced four-factor

model was inspected. However, the results were not consistent

with the four-factor model described by Snoek and colleagues,

who had the following four factors: (1) emotional problems related

to diabetes, (2) treatment problems, (3) food problems, (4) lack of

social support.

18

As can be seen in Table 2, our four-factor solution

was not interpretable, with the exception of factor 1, which had

some resemblance to Snoek and colleagues’ emotional subscale;

but items from the food-related, social support and treatment-

related distress subscales loaded on the same factor.

We also inspected a three-factor and a two-factor model using

EFA; both solutions were not interpretable. The first factor of the

two-factor solution consisted of items assessing ‘diabetes stress’

and a second factor containing items covering not only ‘food-

related problems’ but also covering ‘coping with complications and

being overwhelmed with the diabetes regimens’. The second factor

had item combinations that rendered it difficult to interpret, partly

because of various secondary loadings. Therefore the two-factor

solution was discarded.

Lastly, we examined a one-factor solution. Our data provided

the strongest support for a one-factor model, although it had four

items with low loadings below 0.30 (concerned about food and

eating = 0.11, deprivation regarding food = 0.17, coping with

complications = –0.00 and feeling overwhelmed by your diabetes

= 0.23).The retained items had factor loadings ranging from 0.36

to 0.73. Internal consistency remained high even after removing

Table 2.

One-, two-, three-, four- and five-factor solution for the PAID as reported by 157 Zambian participants (aged 12–68 years) with type 1 and

2 diabetes

Factor solution

One-factor Two-factor

Three-factor Four-factor

Five-factor

Shortened item content

F1 F1 F2 F1

F2 F3 F1 F2 F3 F4 F1 F2 F3 F4 F5

Feeling depressed?

0.71 0.70

0.76

0.75

0.74

Worry about low blood sugar reactions? 0.58 0.62

0.63

0.76

0.77

Worry about complications?

0.70 0.70

0.69

0.68

0.69

Feeling angry?

0.63 0.60

0.74

–0.40 0.72

–0.40

0.71

–0.37

Feeling scared?

0.73 0.73

0.77

0.62

0.63

Feeling discouraged with treatment?

0.73 0.72

0.75

0.64

0.61

Mood related to diabetes?

0.63 0.63

0.54

0.61

0.31

0.59

Feeling ‘burned out’?

0.70 0.67

0.60

0.64

0.53

–0.40

Feelings of guilt or anxiety?

0.65 0.64

0.63

0.55

0.55

Diabetes is taking up too much energy? 0.59 0.54

0.51

0.53

0.57

Uncomfortable social situation?

0.63 0.65

0.60

0.76

0.76

Feeling that others are not supportive?

0.67 0.67

0.55

0.39

0.31 0.63

0.65 –0.31

Feeling alone with your diabetes?

0.62 0.64 0.69

0.72

0.70

Not ‘accepting’ your diabetes?

0.68 0.72

0.63

0.31 0.30

0.51

0.53

Unsatisfied with diabetes physician?

0.56 0.60

0.40

0.64

0.59 0.44

0.53 0.46

Concerned about food and eating?

0.11

0.72

0.73

0.75

0.87

Feelings of deprivation regarding food? 0.17

0.76

0.73

0.79

0.76

Coping with complications?

–0.00

0.69

0.75

0.66

–0.42

0.59 –0.42

Not having clear and concrete goal?

0.36

0.43

0.43

0.38

–0.90

Feeling overwhelmed by your diabetes? 0.23

0.59

0.41 –0.59

0.49 –0.57

–0.79 –0.32

Eigenvalue before rotation

6.69 6.69 2.14 6.69 2.14 1.35 6.69 2.14 1.35 1.14 6.69 2.14 1.35 1.14 1.02

% variance before rotation

33.45 33.45 10.70 33.45 10.70 6.73 33.45 10.70 6.73 5.71 33.45 10.70 6.73 5.71 5.12

Eigenvalue after rotation

6.65 2.39 6.58 2.41 1.78 6.03 2.39 1.55 4.08 5.91 2.11 1.41 4.17 2.22

Principle factor analysis using oblique rotation (direct oblimin).