VOLUME 13 NUMBER 1 • JULY 2016

35

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

RESEARCH ARTICLE

intolerance, questions arise with regard to the possibility of a

connection between under-nutrition and DM.

In general, this study highlights the need to undertake

population-based studies in all districts in the country to quantify

the magnitude of NCDs at a national level. It is evident that

there is variation among ethnic groups and locations, as various

factors contribute to the development of disease and other factors

contribute to the perpetuation of diseases.

In order to institute a cost-effective intervention, the specific

factors at play in a given population must be identified. It may not

be appropriate to generalise these findings to refer to the Karamoja

population. These results though are useful in guiding intervention

and preventative measures for the Kasese population, and should

be well received by policy makers in the local government of Kasese,

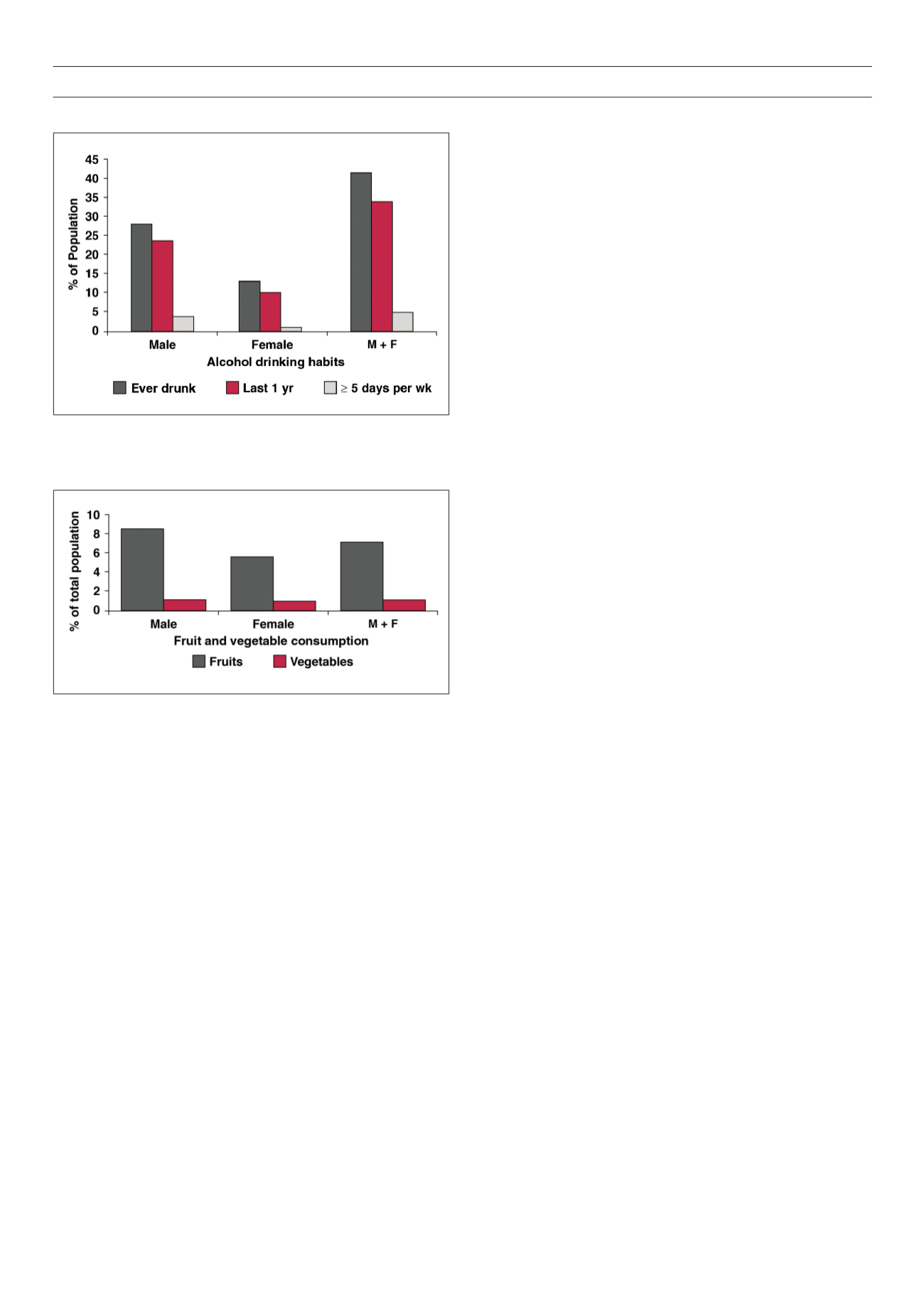

as well as the ministry headquarters. For example, vegetables and

fruits are grown in large quantities in Kasese, but consumption is

low. Most are sold to the cities. The population is not aware of

the benefits to their health of eating fruit and vegetables. Mass

education to encourage increased consumption of fruits and

vegetables will benefit the population.

A key strength of this study was the use of a representative

sample, with analysis taking into account the complex survey

design. The relatively high response level minimises the likelihood of

selection bias, and the range of factors that were measured should

be a good reflection of those factors in the Kasese population. The

use of WHO standardised protocols, intensive training of data-

collection staff, pre-study testing of procedures, and the close

supervision of staff during data collection all highlight the attention

that was paid to minimising avoidable sources of measurement

error.

Limitations of this study need to be borne in mind. The STEPS

methodology is designed to provide standardised information on

key modifiable risk factors that can be measured in population-

based surveys without resorting to high-technology instruments. It

is not designed to measure total energy intake, dietary fat, dietary

sodium, body fatness or physical activity by objective methods,

such as accelerometry and pedometry. Information on these

factors would have provided a more comprehensive picture of the

relationships we studied. In addition, these cross-sectional data do

not allow age-related differences in BP, blood glucose and total

cholesterol levels to be attributed to ageing, independent of cohort

effects. Assessment of risk factors by age group as well as fasting

blood sugar level for different BMIs would have provided more

insight. Finally, due to lack of power, we were not able to assess

the relationship between underweight and diabetes.

Conclusion

This study provides the first NCD risk-factor profile of people in

the Kasese district, Uganda, using internationally standardised

methodology. Our findings for this predominantly rural sample

provide evidence for health policy-makers as well as district

authorities on lifestyle problems in the population studied. The

burden of more diseases is to be expected if an effective prevention

strategy is not undertaken.

Although even short-term educational programmes have been

shown to be effective in improving lifestyle, a durable education

strategy and cost-saving policies supported by sustained large-

scale media education and school-based educational programmes

could be the starting point for a possible national programme on

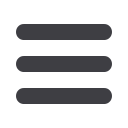

Figure 9.

Alcohol consumption; 41.6% had ever drunk alcohol in life;

34.1% drank in past 12 months; 5.3% of active drinkers ≥ 5 days/wk –

(average number of drinks per day was 3 for men and 2 for women)

Factors not measured in this survey, and which may explain the

observed risk among women, were hormonal status, saturated fat

consumption and salt intake. Also, further studies should be done

to document the proportion of those on treatment whose BP is

under control, as well as the presence of hypertensive heart disease

among those with hypertension.

The second major finding was that the risk profile of this

predominantly rural population of Kasese was markedly different

from that reported previously for the urban and peri-urban

settings.

10-12

The prevalence of raised blood glucose levels (defined

as capillary whole BG of at least 6.1 mmol/l) in 31% of females and

10% of males, DM (13.9% had a family history of DM, 2.9% were

diabetic), raised BMI (15.6% were overweight, 6.7% were obese),

and tobacco smoking (24% had history of smoking with 9.6%

heavy smokers) were markedly higher than previously speculated.

The level of physical activity was surprisingly lower than expected

in this predominantly hilly area, although different definitions of

physical activity could have led to this response. These findings

support the need for regular screening of individuals for NCDs and

their risk factors.

There was a high prevalence of underweight people (29.9%).

When taken together with the observed rates of DM and glucose

Figure 10.

Fruit and vegetable intake; 7.2% of total population ate ≥ 5

servings of fruits per week; 1.2% of total population ate ≥ 5 servings of

vegetables per week