SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

RESEARCH ARTICLE

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 2 • DECEMBER 2017

55

Cameroon

30

and Tanzani,

31

although lower than in ours.

The higher prevalence of overweight, obesity (abdominal and

general) as reflected in WC and mean BMI, hypercholesterolaemia,

alcohol abuse and smoking, being more common in diabetic than

non-diabetic subjects, is however an expected finding, as they

all have individual and associative effects in predisposition to the

development of diabetes.

8,30

Therefore, while diabetes in itself

has been demonstrated to be an independent cardiovascular risk

factor,

32

the impact of its association or cumulative effect with other

traditional risk factors in the development, progression, morbidity

and mortality linked with CVDs cannot be overemphasised.

Limitations and strengths of the study

Our study has several limitations that deserve mention. First the

hospital base of the recruitments and the selected nature of the

participants could have increased the chances that those included

were at high risk for metabolic risk factors, which therefore could

account for the high prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors

in our study. Secondly, the method of diagnosis of hypertension

could be subject to debate, but it has been clearly evidenced by

Burgess

et al

. that failure to carry out multiple measurements to

confirm the diagnosis may lead to false positives.

33

Thirdly, quantity

or concentration of alcohol in the local beer may vary from

one country to another, and we could not assess non-industrial

alcoholic beverages. Lastly, although the overall sample size was

large, the number of patients contributed from each participating

centre within the countries tended to be small, therefore precluding

meaningful centre-level analysis.

In spite of these limitations, the multi-centre, multi-national

character of this study increased our chances of adequately exploring

the prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in the participating

countries, anddemonstratingevidenceof thegrowingcardiovascular

risk factors in this region plagued with communicable diseases. The

use of well-trained data collectors (medical practitioners) also gave

confidence in the measured parameters.

Conclusions

This study reports alarmingly high prevalences of cardiometabolic risk

factors among adults presenting at urban and semi-urban hospitals

in selected countries in SSA, which is in line with IDF projections

of NCDs (hypertension and diabetes mellitus) in the region. It

also raises the question of the influence of rapid urbanisation on

the development of risk factors for imminent cardiovascular and

metabolic diseases. This has considerable public health impact

for an already economically disadvantaged setting to design new

methods or further strengthen existing measures and interventions

for the control of chronic diseases in the region.

We thank all the investigators who participated in data acquisition:

from Madagascar: Rakotoarisoa Bodosoa, Raharimanana Lanto,

RakotoarimananaJeanJacques,RatavilahyRoland,Andrianandrasana

Hery, Rabarijoelina Claude, Rakotoarisoa Holiarivelo, Johanes Abel,

Rakotoniaina Beatrice, Razafindramiandra Jacky, Raheliarisoa

Julia, Rabetrano Alice, Rasolonjatovo Methouchael, Miandrisoa

Rija Mikhael, Rakotozafy Joseline, Raveloarison Marguerite,

Ramiandrisoa Bodovololona, Randriamiarisoa Ny Aina, Raniriharisoa

Voahirana, Rasolofomanana Ndrina, Rasamimanana Nivo Nirina

and Randriantsoa Eric; from Cameroon: Nzundu Anne, Mfulu Papy,

MumbuluErick,ChristianNsimbaLuzolo,MrBoderalFundu,Tswakata

Masam, Iwnga Kabenba, Lepica Bonpeka, Murielle Longokolo,

Tondo, Bandubola Dedie, Kahamba Jean Louis, Massamba Mp Cla,

Loshisha-Armod, Bhuvem, Nzambi Mpvngv Stephane, Jimm Pierre

K and Toure Wenana Parfait; from the Democratic Republic of

Congo: Toko Olivier, Nzundu Annie, Tswakata Masam, Musibisoli

Dieudonne, Longokolo Mireille, Bandubola Dedie, Kahamba Jean-

Louis, Massamba Mpela and Loshisha Arnold.

We also thank the staff of the Clinical Research Education,

Networking and Consultancy (CRENC), Cameroon for their

assistance in data analysis and interpretation, and for drafting the

manuscript. We acknowledge funding support from Sanofi Aventis

pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Kengne AP, Mayosi BM. Readiness of the primary care system for non-

communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Lancet Global Health

2014;

2

(5): e247–248. PMID: 25103156.

2. Mensah GA. The global burden of hypertension: good news and bad news.

Cardiology Clinics

2002;

20

(2): 181–185. PMID: 12119794.

3. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global

burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data.

Lancet

2005;

365

(9455):

217–223. PMID: 15652604.

4. Ataklte F, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Taye B, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Kengne AP. Burden

of undiagnosed hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and

meta-analysis.

Hypertension

2015;

65

(2): 291–298. PMID: 25385758.

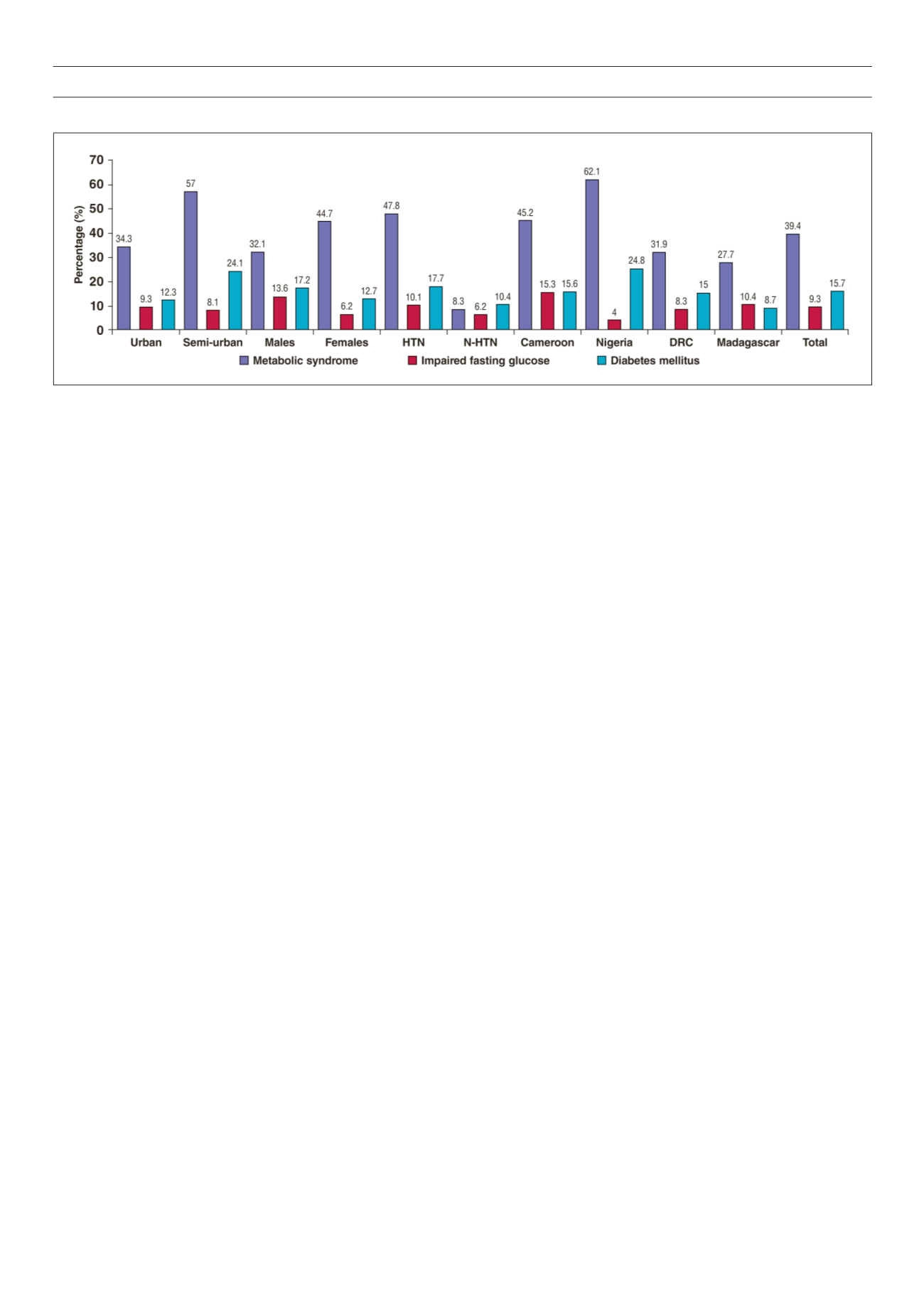

Figure 1.

Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome, impaired fasting glucose levels and diabetes across countries, urbanicity, gender and hypertension status. HTN =

hypertensives, N-HTN = non-hypertensives