VOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 • NOVEMBER 2018

69

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

REVIEW

SGLT-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes

Protecting the kidney (and heart) beyond glucose control

Brian Rayner

Correspondence to: Brian Rayner

Division of Nephrology and Hypertension University of Cape Town

e-mail:

brian.rayner@uct.ac.zaPreviously published by

deNovo Medica,

September 2018

S Afr J Diabetes Vasc Dis

2018;

15

: 69–73

Background

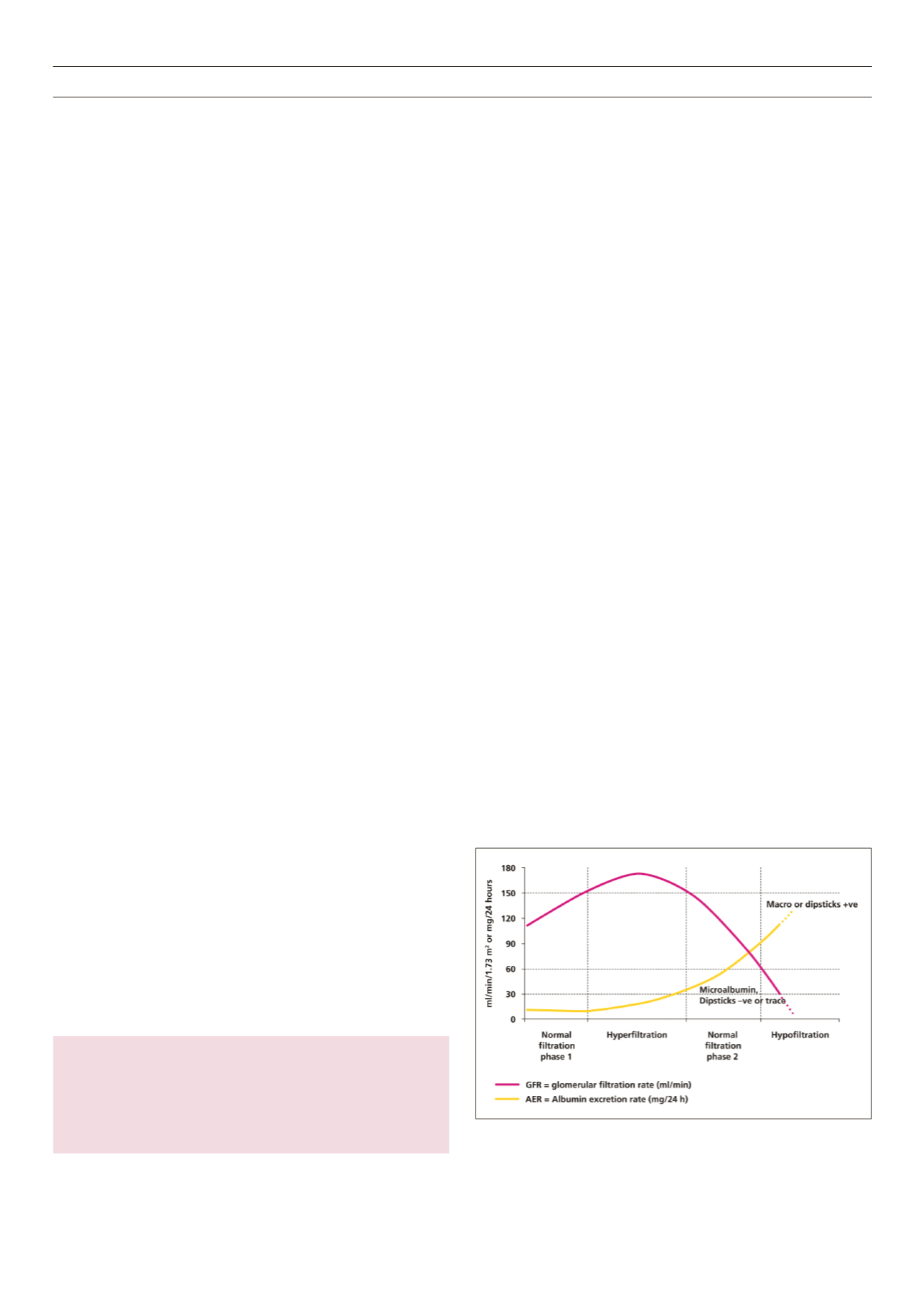

Longstanding diabetes is associated with both macrovascular

(myocardial infarction, stroke and peripheral vascular disease) and

microvascular disease (retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy).

Nephropathy affects approximately 40% of patients with diabetes

and follows a long natural history (Fig. 1), initially manifesting with

an elevated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to poor glucose

control.

1

In time there is a progressive and inexorable decline in

renal function to end-stage renal disease. However, because many

diabetics remain undiagnosed for many years, chronic kidney

disease (CKD) may be present at diagnosis.

Nephropathy is predicted by small amounts of albumin in

the urine (below dipsticks detection) or microalbuminuria that

progressively increases to overt albuminuria associated with loss

of kidney function. In the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes

Study (UKPDS) the progression rate from normoalbuminuria to

microalbuminuria was 2% per year, to macroalbuminuria 2.8%,

and macroalbuminuria to elevated serum creatinine 2.3%.

2

The importance of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is two-

fold. Firstly, it heralds a markedly increased mortality rate with

advancing kidney disease, mainly due to cardiovascular (CV)

disease. The annual death rate for normoalbuminuria is 0.7%,

microalbuminuria 2%, macroalbuminuria 3.5% and elevated

creatinine 12.1%.

2,3

If nephropathy develops at age 30 years,

life expectancy is reduced by 14.8 years in men and 16.9 years

in woman.

4

The reasons for the increased CV risk are complex

and involve both traditional risk factors, especially worsening of

hypertension, and non-traditional risk factors such as vascular

calcification, which is beyond the scope of this article.

Secondly, DKD is now the commonest cause of end-stage CKD

in most countries in the world and South Africa is no exception.

5

Currently 47.2% of dialysis patients in the private sector are

diabetics and the vast majority type 2. In the state sector the

figure is 11.2% and the implication of this is that the majority

of diabetics in the public sector are sent home to die of end-

stage CKD. The cost of dialysis in the private sector is in excess of

R200 000 per annum per patient and accounts for one of the

single biggest expenditures by medical aids in South Africa.

It is abundantly clear that CV disease and DKD are inextricably

linked, and both need to be addressed to reduce the burden of

kidney and associated CV disease.

Current knowledge of prevention and treatment

of DKD

There are many challenges in the treatment of DKD. Firstly, it is

silent and insidious with signs and symptoms only developing in

CKD stages 4 and 5; so late diagnosis is common. There is lack

of public awareness and failure to implement regular screening.

The major modifiable risk factors for DKD are the presence of

microalbuminuria (or incipient nephropathy), hypertension,

smoking, obesity, dyslipidaemia and dietary factors.

It is also critical to understand that small improvements in the

trajectory of GFR can translate into long-term benefits. For example,

by changing the trajectory of loss of GFR from 3 ml/min/year to 2

ml/min/year, the time to end-stage CKD can be increased by up to

10 years or more.

6

All diabetics should have their creatinine, estimated GFR (eGFR),

urine dipsticks, and urine albumin/creatinine ratio performed at

diagnosis andannually. If abnormal, theseneed tobeperformedmore

regularly. Dipsticks positive for albumin, macroalbuminuria, and/or

eGFR < 60 ml/min are very suggestive of DKD. Microalbuminuria

signifies incipient nephropathy and a very elevated eGFR > 120 ml/

min is also a risk factor because of the long-term harmful effects

of hyperfiltration.

Correct performance and interpretation of urinary albumin/

creatinine ratio are essential. Firstly, the urine should be a first

voided overnight specimen to standardise testing. Spot urines

significantly overestimate the presence of albuminuria. Ideally

three specimens need to be obtained, but in practice testing is

usually performed using only one. Normoalbuminuria is an albumin

creatinine ratio < 3 mg/mmol, microalbuminuria 3–30 mg/mmol

and macroalbuminuria > 30 mg/mmol (Table 1). Unfortunately

several laboratories report in gm of albumin to gm of creatinine,

Fig. 1.

Change in kidney function (GFR and albumin excretion) as diabetic

nephropathy progresses.