140

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 4 • NOVEMBER 2014

REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

guidelines leads to significant errors in BP measurement. BP should

be recorded using an approved and calibrated electronic device

or mercury sphygmomanometer (Table 2). Repeat measurements

should be performed on at least three separate occasions within

four weeks unless BP is ≥ 180/110 mmHg.

Self- and ambulatory measurement of BP

Self BP measurement (SBPM) and ambulatory BP measurement (ABPM)

are recommended in selected circumstances and target groups:

11

• suspected white-coat HTN (higher readings in the office

compared with outside) or masked HTN (normal readings in

office but higher outside)

• to facilitate diagnosis of HTN

• to guide antihypertensive medication, especially in high-risk

groups, e.g. elderly, diabetics

• refractory HTN

• to improve compliance with treatment (SBPM only).

Masked HTN should be suspected if, despite a normal BP in the

clinic, there is evidence of target-organ damage.

All devices used for SBPM and ABPM should be properly

validated in accordance with the following independent websites:

www.dableducational.comor

http://afssaps.sante.fr.

In general, only upper-arm devices are recommended, but these

are unsuitable in patients with sustained arrhythmias. For SBPM

the patient should take two early morning and two late afternoon/

early evening readings over five to seven days, and after discarding

the first day readings, the average of all the remaining readings is

calculated.

Wrist devices are recommended only in patients whose arms are

too obese to apply an upper arm cuff. The wrist device needs to be

held at heart level when readings are taken.

The advantages of SBPM measurement are an improved

assessment of drug effects, the detection of causal relationships

between adverse events and blood pressure response, and possibly,

improved compliance. The disadvantages relate to increased patient

anxiety and the risk of self-medication.

ABPM provides the most accurate method to diagnose HTN,

assess BP control and predict outcome.

12

Twenty-four-hour ABPM

in patients with a raised clinic BP reduces misdiagnosis and saves

costs.

13

Additional costs of ABPM were counterbalanced by cost

savings from better-targeted treatment. It can also assess nocturnal

BP control and BP variability, which are important predictors

of adverse outcome. However the assessment is limited by

access to ABPM equipment, particularly in the public sector, and

impracticalities of regular 24-hour ABPM monitoring.

The appropriate cut-off levels for diagnosis of HTN by SBPM and

ABPM are listed in Table 3.

11

Automated office BP measurement

Despite efforts to promote proper techniques in manual BP

measurement, it remains poorly performed. Automated office BP

measurement offers a practical solution to overcome the effects of

poor measurement, bias and white coating.

14

It is more predictive

of 24-hour ABPM and target-organ damage than manual office BP

measurement. Six readings are taken at two-minute intervals in a

quiet room. The initial reading is discarded and the remaining five are

averaged. The appropriate cut-off level for HTN is 135/85 mmHg.

14

CVD risk stratification

The principle of assessing and managing multiple major risk factors

for CVD is endorsed. However, because the practical problems in

implementing previous recommendations based on the European

Society of HTN (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)

HTN guidelines, it has been decided to use a modification of this

approach.

9

Once the diagnosis of HTN is established, patients with BP ≥

160/100 mmHg should commence drug therapy and lifestyle

modification. Patients with stage 1 HTN should receive lifestyle

modification for three to six months unless they are stratified as

high risk by the following criteria: three or more major risk factors,

diabetes, target-organ damage or complications of HTN (Table 4).

Routine baseline investigations

Table 5 lists recommended routine basic investigations. The tests

are performed at baseline and annually unless abnormal. Abnormal

results must be repeated as clinically indicated.

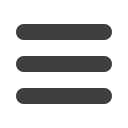

Table 3.

Definitions of hypertension by different methods of BP

measurement

Office

Automated

office

Self

Ambulatory

Predicts

outcome

+

++

++

+++

Initial diagnosis

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Cut-off BP

(mmHg)

140/90

Mean

135/85

135/85 Mean day

135/85

Mean night

120/70

Evaluation of

treatment

Yes

Yes

Yes

Limited, but

valuable

Assess diurnal

variation

No

No

No

Yes

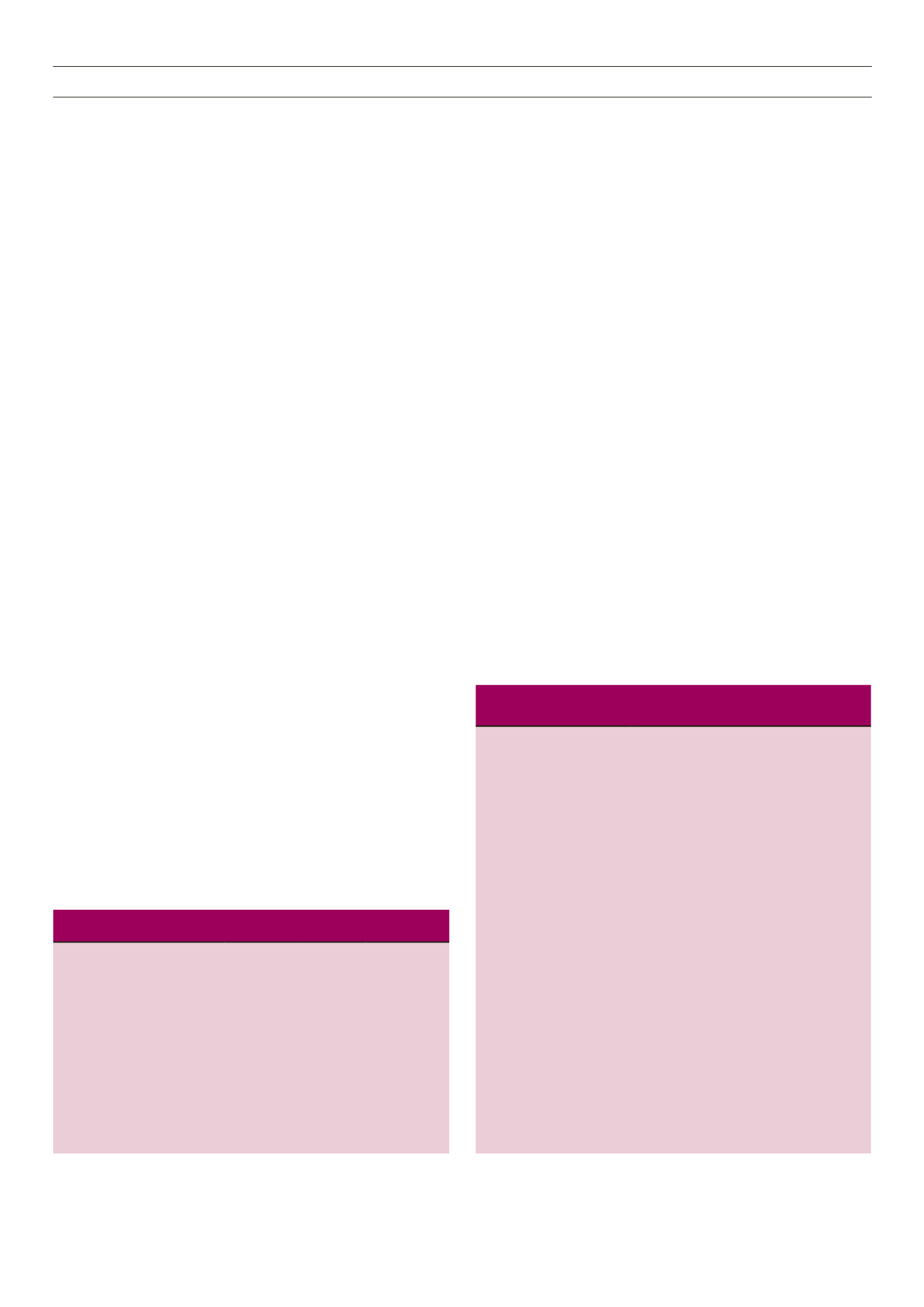

Table 4.

Major risk factors, target-organ damage (TOD) and

complications. Adapted from the ESH/ESC guidelines

9

Major risk factors

TOD

Complications

• Levels of systolic and

diastolic BP

• Smoking

• Dyslipidaemia:

– total cholesterol

> 5.1 mmol/l, OR

– LDL > 3 mmol/l, OR

– HDL: men < 1 and

women < 1.2 mmol/l

• Diabetes mellitus

– Men > 55 years

– Women > 65 years

• Family history of early

onset of CVD:

– Men aged < 55 years

– Women aged

< 65 years

• Waist circumference:

abdominal obesity:

– Men ≥ 102 cm

– Women ≥ 88 cm

The exceptions are

South Asians and

Chinese:

men: > 90 cm and

women: > 80 cm.

• LVH: based on

ECG

– Sokolow-Lyons

> 35 mm

– R in aVL

> 11 mm

– Cornel

> 2 440 (mm/

ms)

• Microalbuminuria:

albumin creatine

ratio 3–30 mg/

mmol, preferably

spot morning

urine and eGFR

> 60 ml/min

• Coronary heart

disease

• Heart failure

• Chronic kidney

disease:

– macroalbuminuria

> 30 mg/mmol

– OR eGFR

< 60 ml/min

• Stroke or TIA

• Peripheral arterial

disease

• Advanced

retinopathy:

– haemorrhages OR

– exudates

– papilloedema