VOLUME 11 NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2014

123

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

REVIEW

Therefore, one of the major initial steps was to conduct

extensive validation studies of the Framingham and UKPDS CVD

risk models, using the unique features of the ADVANCE cohort.

3

These validation studies revealed that, in the cohort of ADVANCE

participants who had no known history of CVD at their enrolment

in the trial, the four-year absolute risk of cardiovascular events

and components was largely overestimated by the Framingham–

Anderson,

30

Framingham–D’Agostino

31

and UKPDS risk models.

9,19

This overestimation was also observed in men and women,

Caucasians and non-Caucasians, and the double-placebo cohort

(i.e. those assigned to the placebo group in the blood pressure-

lowering arm and the standard-care group of the blood glucose

control arm).

3

Discrimination of the Framingham and UKPDS risk models

in predicting CVD events in ADVANCE was poor for stroke, and

modest to acceptable for coronary heart disease and total CVD.

Recalibration substantially attenuated the magnitude of risk

overestimation by the Framingham and UKPDS risk models in

ADVANCE. Discrimination was unaffected as expected, indicating

the need for newCVD risk models with improved predictive accuracy

for people with diabetes, particularly those who are receiving many

contemporary cardiovascular riskreducing therapies.

Development of the ADVANCE cardiovascular risk

model

In developing a new model for risk prediction, it is critical to account

for the limitations of existing ones in order to improve performance.

The inclusion in ADVANCE of participants from many countries

provided the opportunity to account for the substantial variation

in the care of diabetes and CVD around the world. Available

models so far had been derived from homogenous populations.

The ADVANCE model targets total CVD and therefore captures the

interrelation between components of CVD such as CHD or stroke,

unlike many existing models that have focused specifically on these

components.

Thecomplexityoftherelationshipbetweenchronichyperglycaemia

and cardiovascular risk has been less fully addressed in existing

models. Some improvement was achieved in the ADVANCE model

through integration of risk factors to capture both the exposure to

chronic hyperglycaemia prior to and after the clinical diagnosis of

diabetes. Statistical method is an important component of model

development. Trusted statistical methods were used to select the

potential risk factors and test their suitability for inclusion in the

ADVANCE risk model.

14

Risk factors considered for inclusion in the ADVANCE model

were: age at clinical diagnosis of diabetes, duration of diagnosed

diabetes, gender, blood pressure (BP) indices [systolic BP, diastolic

BP, mean arterial (MAP) and pulse (PP) pressures], lipid variables

[total, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and non-HDL cholesterol, ratio

of total:HDL cholesterol and triglycerides], body mass index (BMI),

waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, BP-lowering medication

(i.e. treated hypertension), statin use, current smoking, retinopathy,

atrial fibrillation (past or present), urinary albumin:creatinine ratio

(ACR), serum creatinine (Scr), HbA

1c

and fasting blood glucose

levels, and randomised treatments (BP lowering and glucose control

regimens).

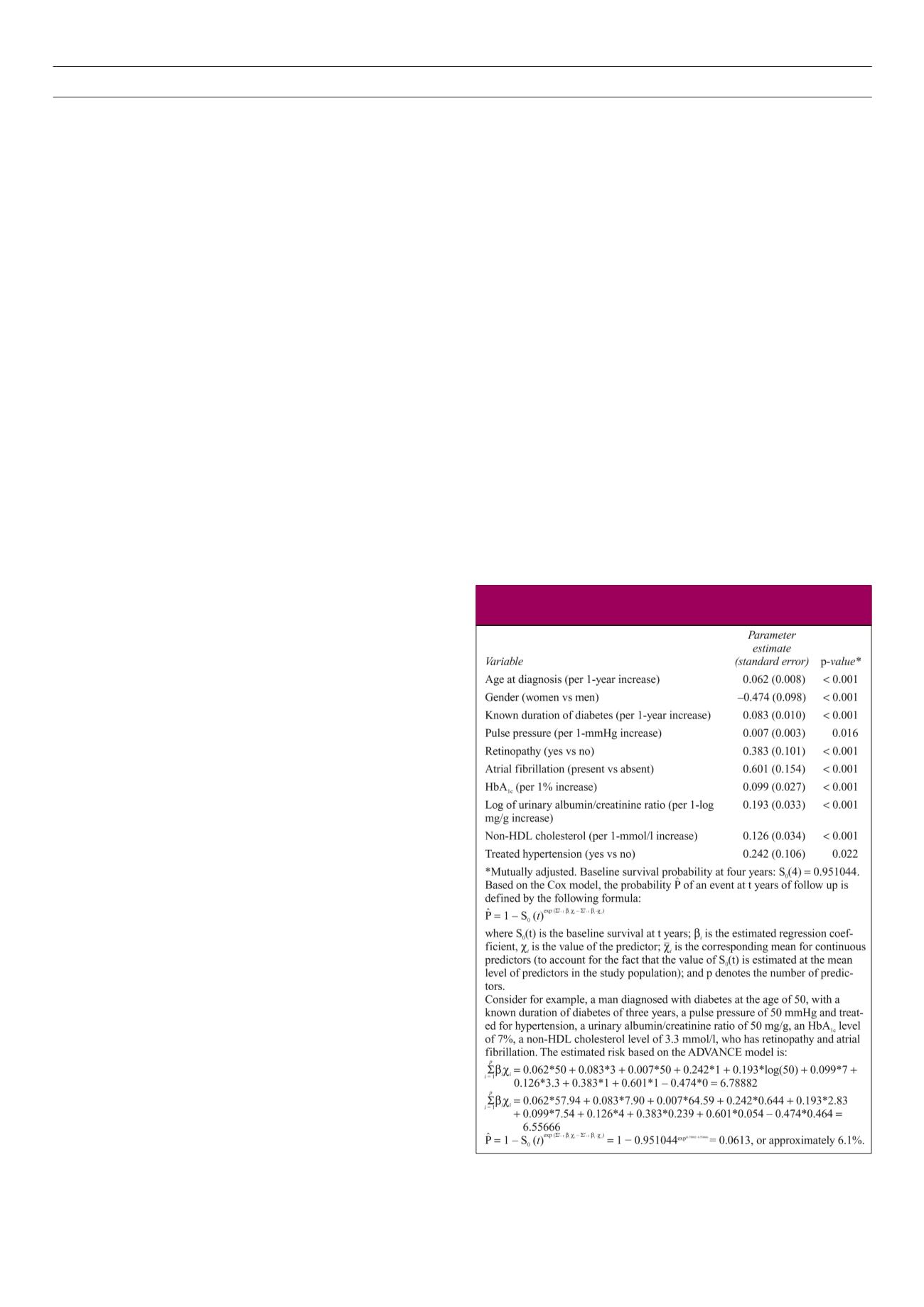

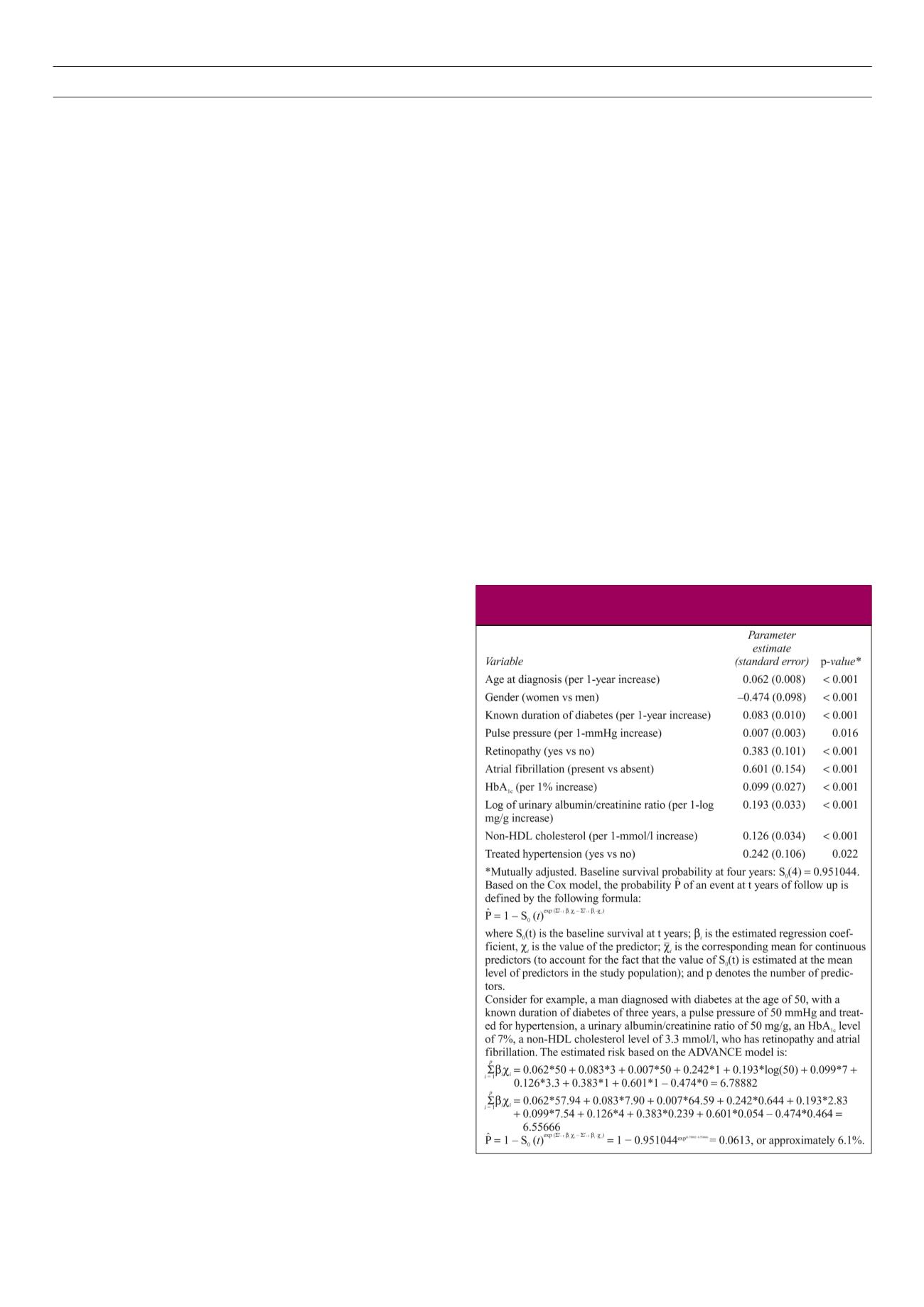

Ten of these candidate risk factors were included in the final

ADVANCE risk model. Age at diabetes diagnosis and known

duration of diabetes were preferred to age at baseline to improve

the applicability of the ADVANCE risk model to other populations.

The beta coefficients and accompanying standard error for risk

factors in the ADVANCE risk model are shown in Table 1.

14

Performance of the ADVANCE risk model

The applicability of the ADVANCE risk model

14

was tested on the

same population used to develop the model (i.e. internal validation)

and on an independent external sample for which the DIAB-

HYCAR cohort

32

was used. In both internal and external validations,

the discrimination of the ADVANCE model was acceptable. In

comparison with existing total CVD models, the ADVANCE model

largely outperformed the Framingham–Anderson and Framingham

D’Agostino models. The calibration of the ADVANCE model was

excellent in internal validation and good in external validation, with

only a modest risk underestimation. This is likely explained by the

difference in the levels of preventive therapies between ADVANCE

and DIABHYCAR population.

Interestingly, the agreement between predictions by the

ADVANCE models and the observed CVD events was consistent

across different cut-off points or predicted risk for CVD. For

comparison, the two Framingham equations overestimated the risk

of CVD in the DIAB-HYCAR cohort by 65% (Anderson equation)

and 99% (D’Agostino equation). Using a cut-off point for four-

year predicted risk of ≥ 8% (which is approximately equivalent to

a 10-year predicted risk of 20% and above), the ADVANCE model

Table 1.

BETA coefficients (95% confidence interval) and standard

errors for predictors in the advance CVD prediction model

14