RESEARCH ARTICLE

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

46

VOLUME 17 NUMBER 2 • NOVEMBER 2020

DM should undergo close follow up and screening for glucose

metabolism disorders.

18

Current recommendations emphasise the

use of OGTT and glycated haemoglobin as screening tests.

26

In a

study conducted in South Africa among patients with CAD, the

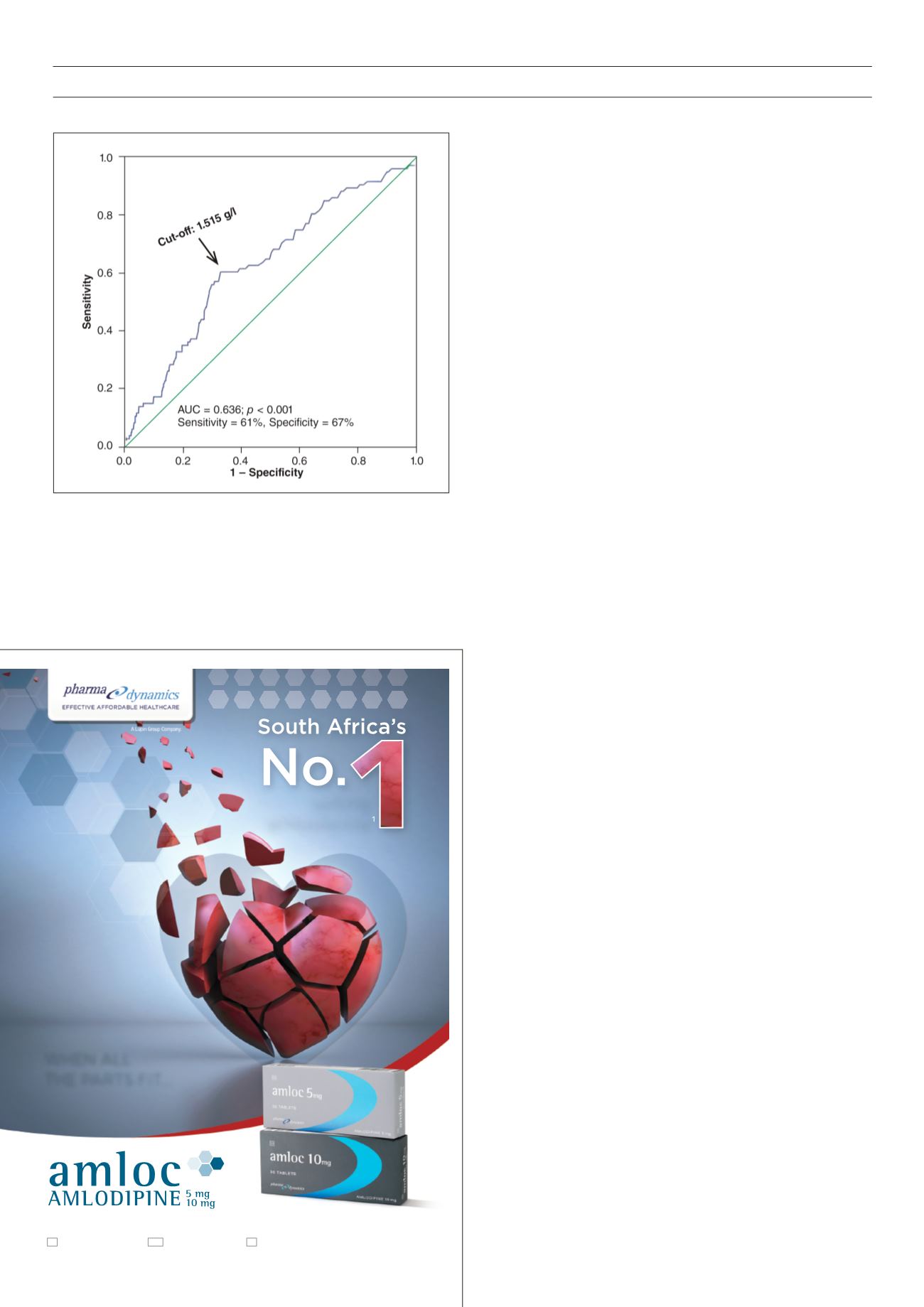

Fig. 1.

ROC curve showing glycaemia cut-off value predictive for in-hospital

death.

rate of IGT measured by OGTT was 30% higher than the rate of

DM (20%).

27

This study included a small sample of patients, but

highlights the need for screening of glucose metabolism disorders

in patients with CAD in our practice.

The other predictors for in-hospital death identified in our study

(age, heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, sustained ventricular

tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation) are powerful prognostic factors

in ACS patients, consistent with studies in developed countries.

6

Dyslipidaemia appeared to be a protective factor, and this

observation has already been reported.

28

It is mainly the influence

of previous lipid-lowering drugs in patients with high cardiovascular

risk that would have a beneficial effect on mortality rate.

28

Previous

treatments in our study were not specified.

PCI was a protective factor in our series but remarkably, only

in patients without a history of DM in sub-group analyses. First,

the low rate of PCI in our patients with ACS

29

is a potential bias.

Second, CAD patients with DM frequently have multi-vessel

coronary heart disease (28.9%) and complex lesions (39.7%),

30

as in studies conducted in developed countries.

31

Coronary artery

bypass graft surgery is often the technique of choice for complete

revascularisation in patients with DM,

32

but is of limited practice in

sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, DM patients are often high-risk patients

in whom an earlier invasive strategy should be implemented.

However, the excessive admission delays

11

determine the low rate

of PCI, which would weaken its beneficial effect.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. Incomplete medical records did not

allow us to make a thorough analysis. Glycated haemoglobin was

not available for all patients and was not included in our analysis,

nor was the evolution of blood glucose levels during hospitalisation.

The influence of previous treatments (antidiabetic drugs, statins)

and glucose-lowering treatments given during hospitalisation

(particularly insulin infusion) have not been specified. Finally, the

low rate of coronary angiography did not make it possible to assess

the link between blood glucose levels and the severity of CAD.

Conclusion

This study, carried out in a sub-Saharan African population, shows

that in the acute phase of ACS, admission blood glucose has a

powerful prognostic value on mortality rate, in accordance with

studies conducted in the West. In association with conventional

treatment of ACS, adequate control of blood glucose is an

important treatment target, especially in non‐diabetic patients.

Routine screening for glucose metabolism disorders and follow up

after ACS must be implemented, as recommended.

26

It would be

interesting to determine the rate of IGT and DM in ACS patients

without a history of DM in the post-discharge phase, and assess the

long-term impact of glucose-lowering therapy on morbidity and

mortality rates.

References

1. Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Krumholz HM, Xiao L, Jones PG, Fiske S,

et al.

Glucometrics in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction-defining

the optimal outcomes-based measure of risk.

Circulation

2008;

117

(8): 1018–

1027

2. Zhao S, Murugiah K, Li N, Li X, Xu ZH, Li J,

et al.

Admission glucose and in-hospital

mortality after acute myocardial infarction in patients with or without diabetes: a

cross-sectional study.

Chin Med J

2017;

130

: 767–775.

3. Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Karthikeyan G, Mazzotta G, Del Pinto M, Repaci S,

et al.

selling

amlodipine

AMLOC 5, 10 mg.

Each tablet contains amlodipine maleate equivalent to 5, 10 mg amlodipine respectively.

S3 A38/7.1/0183, 0147. NAM NS2 06/7.1/0011, 0012. BOT S2 BOT 0801198, 0801199. For full prescribing

information, refer to the professional information approved by SAHPRA, 29 September 2017.

1)

IQVIA MAT

UNITS August 2019.

ACF622/10/2019

.

CUSTOMER CARE LINE

0860 PHARMA (742 762)

www.pharmadynamics.co.zaWHEN ALL

THE PARTS FIT...

PERFECTLY.