94

VOLUME 10 NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2013

REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

18–25 years in Oxford found rates of 8–26%, depending upon the

diagnostic criteria used for PCOS.

15

More recently, an Australian

community study (

n

=728) compared PCOS prevalence using three

different sets of diagnostic criteria: the NIH 1990,

16

Rotterdam

Consensus

17

and the Androgen Excess Society.

18

The women were

predominantly European (94%) with a mean BMI of 25.7 kg/m.

2

Prevalence rates were 17.8% using Rotterdam criteria, and 70%

of these women were previously undiagnosed.

1

The findings

suggest that the actual prevalence of PCOS could be considerably

higher than the frequently quoted 6–10% figure, due to different

diagnostic criteria and under-diagnosis in primary care. This poses

a considerable obstacle if PCOS is to be used as a basis for CMD

screening in clinical practice.

PCOS and obesity

Numbers of women with PCOS appear to be increasing, and this

might indicate increasing prevalence.

19

A link has been reported

between the increasing incidence of obesity, IGT and type 2 diabetes

amongst adolescent girls with PCOS.

20

It is therefore plausible that

the population rise in BMI might be increasing the prevalence of

PCOS, since obesity is known to increase hyperandrogenism

21

and

menstrual irregularity.

21,22

Of potential significance is the associated

increase in insulin resistance observed in these women.

23–25

Several

studies suggest that PCOS may be a specific manifestation of

insulin resistance,

6

and that insulin resistance is present in the

majority.

26

Thus, it would not be surprising if the global rise in

obesity is increasing the prevalence of PCOS and associated

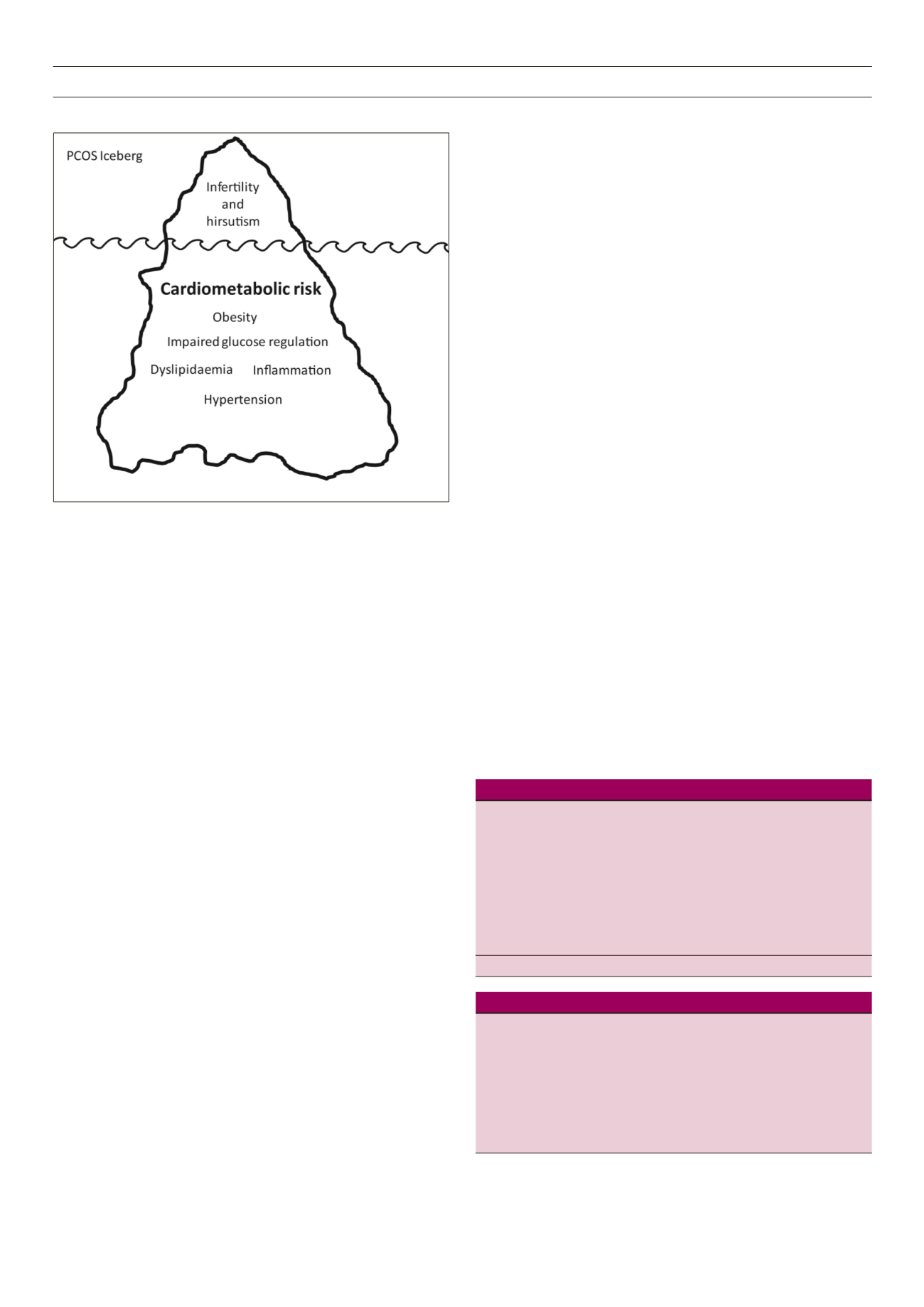

CMD linked to insulin resistance. However, it is likely that women

currently diagnosed with PCOS are the tip of a very large iceberg

with the majority of PCOS and the co-existing CMD unrecognised

and untreated (Figure 1).

Current guidance on screening for type 2 diabetes in women

with PCOS

Both DUK and the ADA recommend that women diagnosed with

PCOS are screened for type 2 diabetes, although US guidance

suggests screening if women have a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m,

2

whereas DUK

suggest screening if BMI ≥ 30 kg/m

2.2,3

Currently, neither DUK nor

ADA provide guidance on the optimal screening test for type 2

diabetes inwomenwith PCOS, the screening interval or interventions

to reduce women’s health risks. There is a need for evidence-based

guidelines on screening, diagnosis and interventions to reduce CMD

specifically in women with PCOS. Current screening guidelines are

based upon evidence extrapolated from studies of older, mixed sex

populations whereas PCOS is a condition of women in reproductive

years and therefore quite clearly distinct.

Controversies in screening and diagnosis of PCOS

Several different sets of diagnostic criteria are used to define PCOS,

and the lack of consensus causes confusion and undoubtedly

contributes to under-diagnosis and difficulties in determining whom

to screen for CMD. The three main sets of criteria are as follows.

The NIH 1990 criteria

There was no agreed definition of PCOS until the NIH 1990

conference sought consensus expert opinion through questionnaires

and debate, producing the first PCOS diagnostic criteria.

16

Although

the term ‘PCOS’ itself implies that PCO should be an essential

feature for diagnosis, this was controversial and ‘polycystic ovaries’

were not included in the final NIH criteria (Table 1).

Using NIH classification, women with hyperandrogenism and

regular menstrual cycles, and women with PCO, irregular menstrual

cycle but no hyperandrogenism, would not be diagnosed as

having PCOS. There was concern that these criteria could result

in false negative diagnoses, missing those with regular cycles,

hyperandrogenism and PCO. The debate over the use of ‘polycystic

ovaries’ as a diagnostic criterion continued until 2003 when a

conference in Rotterdam proposed different criteria.

17

The Rotterdam (ESHRE) 2003 criteria.

In 2003 the ESHRE/ASRM

developed what are now known as the ‘Rotterdam criteria’. These

added two new phenotypes by including the feature of PCO in the

diagnostic criteria (Table 2):

Table 1.

The NIH 1990 criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS.

A diagnosis of PCOS may be made if there is both:

i. Presence of hyperandrogenism with either clinical signs (hirsutism, acne,

or male pattern balding) or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenemia

(high serum androgen concentrations) and

ii. Presence of chronic menstrual irregularity due to oligomenorrhoea/

amenorrohoea

after

iii. Excluding other known disorders such as Cushing’s syndrome,

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumours, and hyper-

prolactinaemia

PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome.

Table 2.

The Rotterdam 2003 criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS.

A diagnosis of PCOS may be made if any two of the following features are

present:

i. The presence of menstrual irregularities – oligomenorrhoea and/or

annovulation

ii. The presence of clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism

iii. The presence of polycystic ovaries

after

iv. Excluding other potential causes of menstrual irregularity or hyper-

androgenism

IcebergTomlinson and Pinkney ©2013

Figure 1.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) iceberg.