100

VOLUME 10 NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2013

REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

Intermittent fasting: a dietary intervention for prevention

of diabetes and cardiovascular disease?

James E Brown,Michael Mosley, Sarah Aldred

Abstract

Intermittent fasting, in which individuals fast on consecutive

or alternate days, has been reported to facilitate weight loss

and improve cardiovascular risk. This review evaluates the

various approaches to intermittent fasting and examines the

advantages and limitations for use of this approach in the

treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Keywords

: diet, fasting, intermittent fasting, obesity, type 2

diabetes, weight loss

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes in recent

decades has been associated with increased comorbidities including

atherosclerotic macrovascular disease and premature mortality.

1–3

Individuals with sub-diabetic degrees of hyperglycaemia, such as

impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and impaired fasting glucose

(IFG) are also at increased risk of premature cardiovascular disease,

emphasising the importance of interventions to improve glucose

homeostasis in pre-diabetic, as well as diabetic individuals.

4–5

Several large studies have identified pre-diabetic individuals

as subjects in whom to investigate lifestyle changes to prevent

the progression to a fulminant diabetic state.

6–10

However, there

is considerable debate regarding the most effective manner in

which lifestyle changes such as diet and/or exercise should be

implemented.

11

The approach of intermittent fasting is currently

generating particular interest.

Intermittent fasting

Extensive evidence suggests that imposing fasting periods upon

experimental laboratory animals increases longevity, improves health

and reduces disease, including such diverse morbidities as cancer,

12,13

neurological disorders

14-17

and disorders of circadian rhythm.

18,19

The

specific benefit of intermittent fasting as a health-giving therapeutic

approach has been recognised since the 1940s.

20

Correspondence to: Dr James E Brown

Aston Research Centre for Healthy Ageing and School of Life and Health

Sciences, Aston University, Birmingham, B4 7ET, UK.

e-mail:

Michael Mosley

Aston Research Centre for Healthy Ageing & School of Life and Health

Sciences, Aston University, Birmingham, UK

Sarah Aldred

School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, College of Life and Environmental

Sciences, University of Birmingham, UK

Originally in:

Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis

2013;

13

(2): 68–72

S Afr J Diabetes Vasc Dis

2013;

10

: 100–102

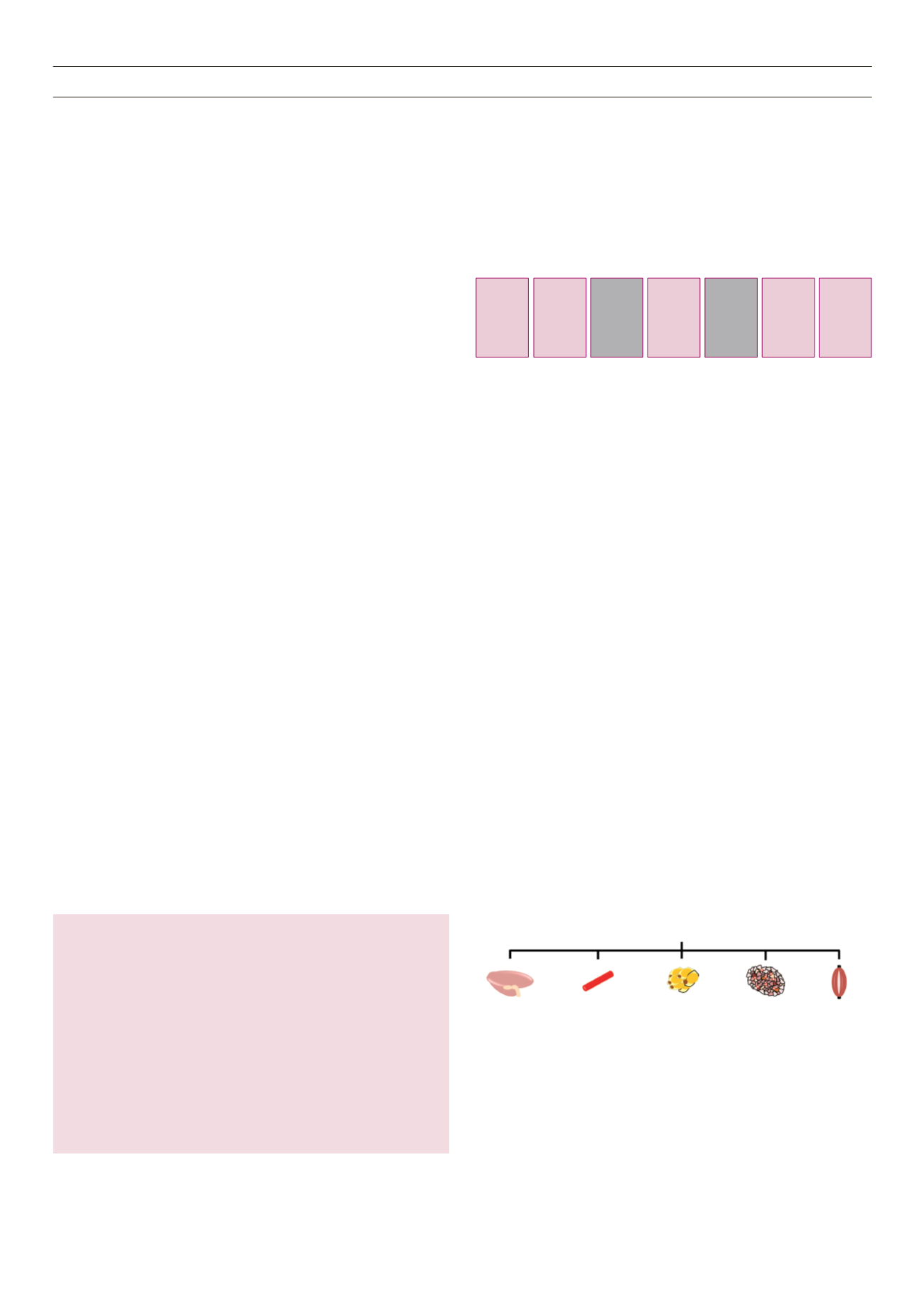

Intermittent fasting can be undertaken in several ways but

the basic format alternates days of ‘normal’ calorie consumption

with days when calorie consumption is severely restricted. This

can either be done on an alternating day basis, or more recently a

5:2 strategy has been developed (Figure 1), where two days each

week are classed as ‘fasting days’ (with < 600 calories consumed

for men, < 500 for women). Importantly, this type of intermittent

fasting has been shown to be similarly effective or more effective

than continuous modest calorie restriction with regard to weight

loss, improved insulin sensitivity and other health biomarkers.

1,21

Fasting has been used in religion for centuries. For example, the

Daniel fast is a biblical partial fast that is typically undertaken for

three weeks, and during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Muslim

calendar, there is a month of fasting during daylight hours, during

which some observers also refrain from fluid consumption.

22

Such

periods of fasting can limit inflammation,

23

improve circulating

glucose and lipid levels

24–27

and reduce blood pressure,

28

even when

total calorie intake per day does not change, or is only slightly

reduced. Ethical and logistical constraints have restrictedmost caloric

deprivation studies to six months, although some have assessed the

effects for longer.

29–31

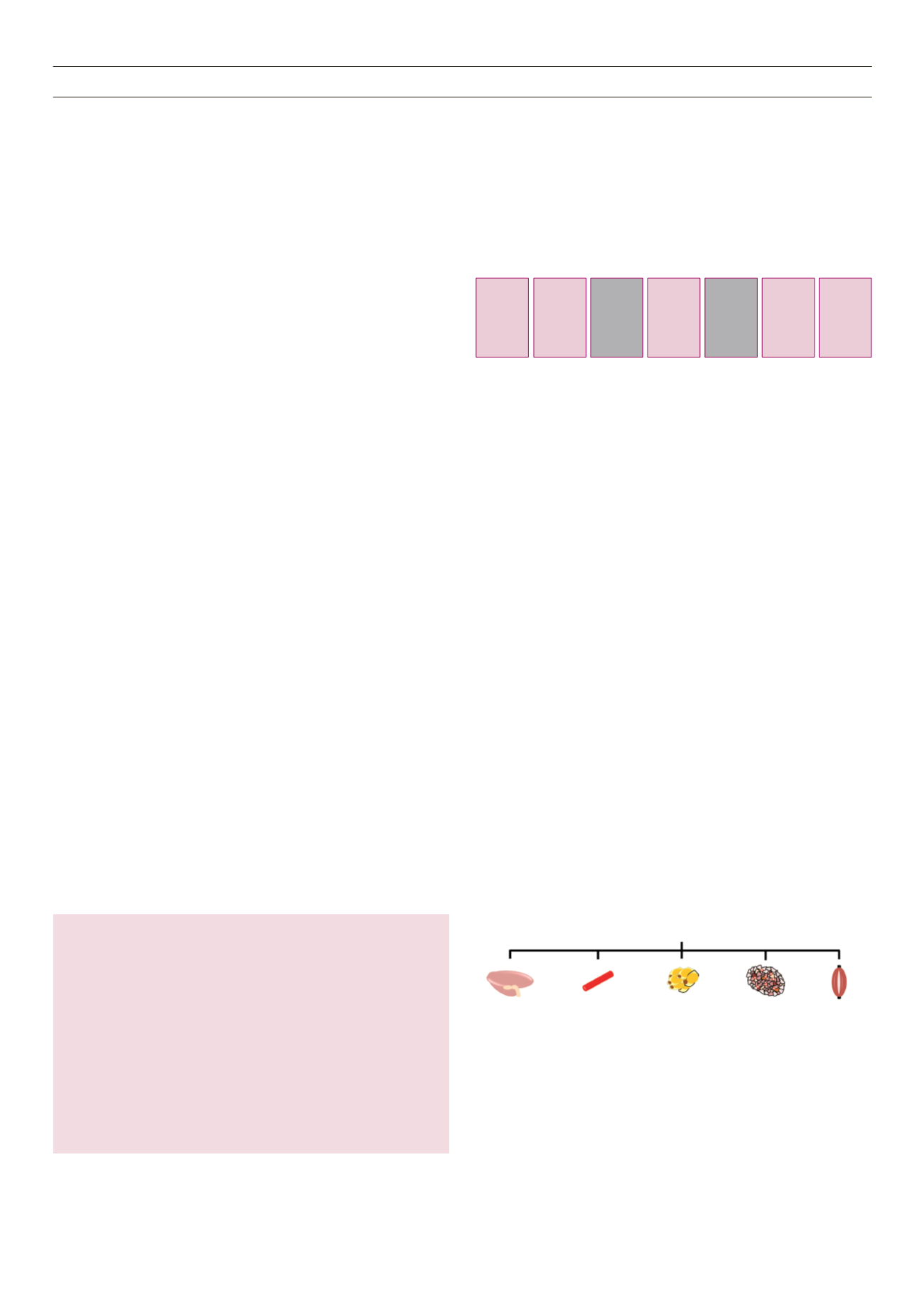

The majority of studies show positive effects

on markers of metabolic health and body composition, in part due

to the demonstrated effects intermittent fasting has on metabolic

tissues (Figure 2). In addition caloric restriction studies undertaken

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of a typical intermittent fasting plan.

Subjects who undertake this form of diet are required to limit their calorie intake

for two days, consecutively or otherwise each week. The calorie limit for fast-

ing days is approximately 25% of TDEE or 600 calories for men and 500 for

women. On non-fasting days subjects can eat normally to their TDEE calorie level

(approximately 2 500 for men and 2 000 for women).

Day 1

Normal

TDEE

Day 2

Normal

TDEE

Day 3

Fasting

500 (female)

600 (male)

Day 4

Normal

TDEE

Day 5

Fasting

500 (female)

600 (male)

Day 6

Normal

TDEE

Day 7

Normal

TDEE

Calories (per day)

TDEE = total daily energy expenditure

Figure 2.

Tissue-specific effects of intermittent fasting and calorie restriction.

Research has identified several biological effects of intermittent fasting and/or

calorie restriction on tissues that are central to metabolic and cardiovascular

health. NO: nitric oxide, TAG: triacylglycerides.

Fasting/calorie restriction

Liver

i

Fatty liver

h

Insulin

sensitivity

Blood vessels

h

No

i

Oxidative

stress

Adipose

tissue

h

Tag deposition

h

Insulin sensitivity

Pancreatic

islet

i

Age related

decline

Skeletal

muscle

h

Glucose

uptake

i

Insulin

resistance