REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

144

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 4 • NOVEMBER 2010

Diabetes mellitus

The association between diabetes mellitus and cognitive decline

is supported by evidence from biochemistry, neuroimaging and

pathology. The hyperglycaemia-induced mitochondrial superoxide

overproduction leads to glucose-mediated microvascular damage.

8

A dysfunction of the insulin-degrading enzyme may result in both

hyperinsulinaemia and accumulation of cerebral amyloid protein

b

, thus providing an association between diabetes and dementia.

9

Diabetes often develops in the context of the metabolic syndrome,

leading to the indirect ischaemic effects of diabetes-associated

cerebrovascular disease.

10

MRI studies revealed a higher frequency of

brain atrophy and a reduced volume of memory-relevant structures

(hippocampus, amygdala) in diabetic patients.

11,12

A large autopsy

study detected more microvascular infarcts and an activation of

neuro-inflammation in demented patients with diabetes.

13

Studies

Initial evidence regarding an association between diabetes and

cognitive dysfunction was derived from several smaller case-control

studies. Though these studies had some methodological problems,

they demonstrated poorer performance in diabetic patients in at

least one aspect of cognitive function, mostly verbal memory.

14

A systematic review of 14 longitudinal population-based studies

assessing the incidence of cognitive decline revealed a higher

incidence of dementia in the majority of studies but also criticised

the lack of relevant confounders such as hypertension, stroke and

glycaemic control.

15

Additional prospective studies accounting for

these deficits have been published and add further evidence that

diabetes is an independent factor in cognitive decline (Table 1).

In the Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group which included

9 679 older women, controlled for several confounding factors

and showed that diabetes was associated with greater cognitive

decline.

16

The Nurses’ Health Study followed 16 596 women, aged

70–81 years, for two years and included details about treatment

and duration of diabetes. The study showed an increased risk of

poor cognition among women who had had diabetes for

>

15

years (OR 1.52; 95% CI 1.15–1.99) and for women not using any

medication (OR 1.45; 95% CI 1.04– 2.02).

17

Use of oral antidiabetic

therapy may reduce risk of cognitive decline as diabetic women

treated with these agents performed similarly to women without

diabetes (OR 1.06 and 0.99).

17

In a sub-analysis of data from a

four-year randomised trial of raloxifene among 7 027 osteoporotic

postmenopausal women the risk of developing cognitive impairment

among diabetic women was almost doubled.

18

The Physicians’

Health Study II with 5 907 men and the Women’s Health Study

with 6 326 women revealed that participants with longer duration

of diabetes (

>

5 years) had generally a greater cognitive decline.

19

More recent trials like the Washington Heights–Inwood Columbia

Aging Project focused on the relationship of diabetes to MCI and

found a higher risk of amnestic MCI among diabetic participants.

20

Hypoglycaemic episodes are an important barrier to the

achievement of optimal glycaemic control. A large cohort study

with 16 667 elderly diabetic people showed an association with

the number of severe hypoglycaemic episodes and increased risk

of dementia.

21

In contrast, a smaller study found no contribution

of hypoglycaemic episodes to cognitive impairment, but reported a

higher risk of hypoglycaemia in patients with dementia.

22

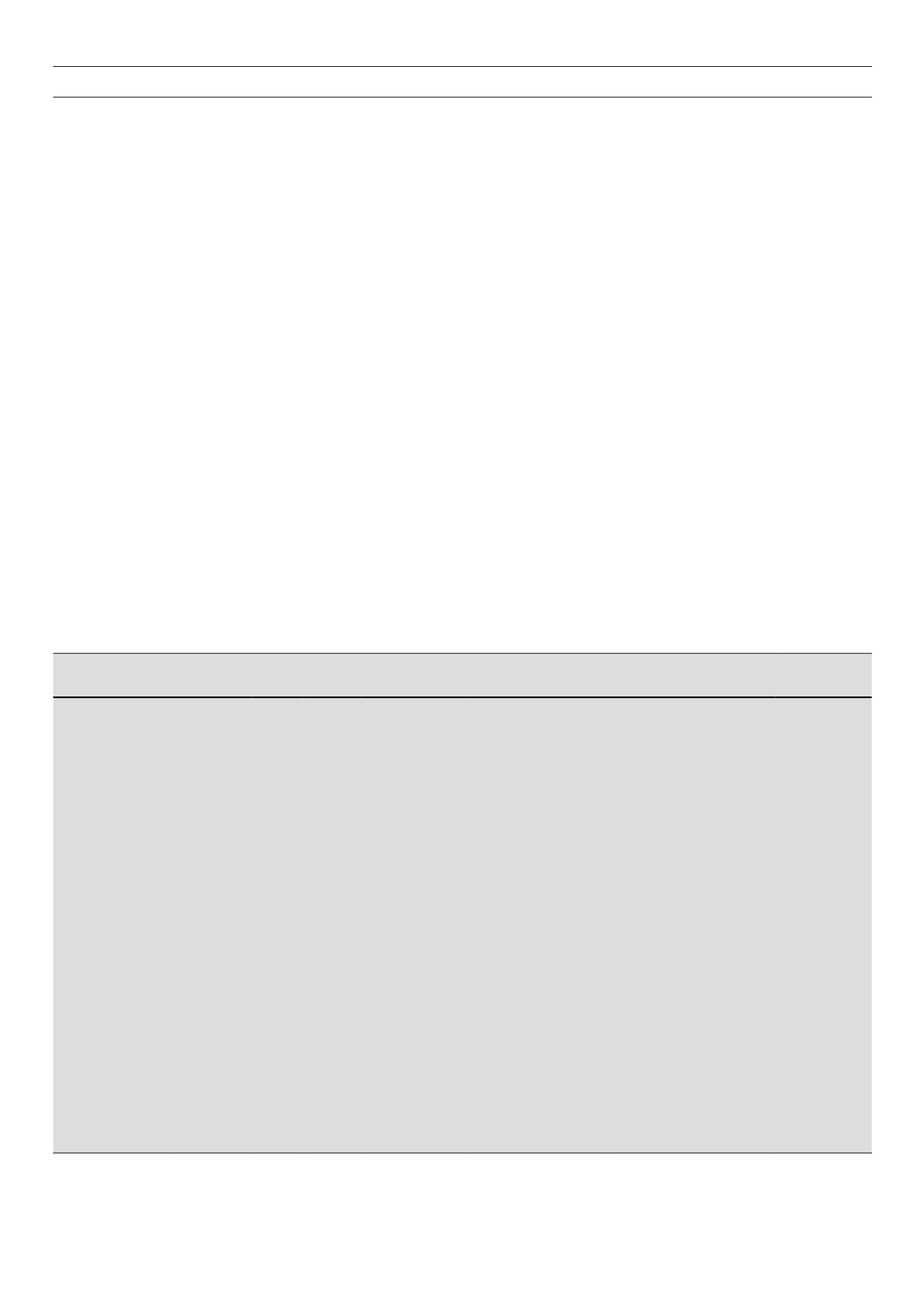

Table 1.

Summary of major prospective studies of the association of diabetes mellitus and cognitive performance.

Study

Participants Mean

age

(years)

Follow-

up

(years)

Cognitive test

Assessment of

diabetes

Covariates

Result (OR/

HR; 95% CI)

for cognitive

decline in

diabetes

Osteoporotic

Fractures Research

Group

16

9 679

♀

>

65 3–6

Digit symbol test,

Trails B and MMSe

at baseline

Self-report

Age, education, depression,

stroke, visual impairment,

heart disease, hypertension,

physical activity, oestrogen use

and smoking

1.63; 1.20–2.23

Nurses’ Health

Study

17

16 596

♀

74.2 2

Telephone

interview for

cognitive status

Self-report

Age, education, duration and

medication of DM

1.34; 1.14–1.57

Multiple Outcomes

of Raloxifene

Evaluation

18

7 027

♀

66.3 4

Five cognitive tests

at baseline and

after four years

Self-report

+

antidiabetic

medication

+

increased

fasting glucose

Age, education, race,

depression

1.79; 1.14–2.81

Physicians’ Health

Study

+

Women’s

Health Study

19

5 907

♂

+

6 326

♀

♂

74.1;

♀

71.9

♂

2;

♀

4

Telephone

interview for

cognitive status

Self-reported

questionnaire

Age, education and hormone

use (women), baseline score,

BMI, hypertension, cholesterol,

depression, smoking, alcohol,

physical activity

–0.74; –1.05

to –0.43 mean

difference of

decline in DM

Washington

Heights– Inwood

Columbia Ageing

Project

20

918

75.9 6

Complete

neuropsychological

testing

Self-report or

antidiabetic medication

Age, sex, education, ethnic

group, apo E, hypertension,

LDL, smoking, stroke, heart

disease

1.4; 1.1–1.8

apo E

=

apolipoprotein E; BMI

=

body mass index; CI

=

confidence interval; DM

=

diabetes mellitus; HR

=

hazard ratio; LDL

=

low-density lipoprotein; MMSe

=

mini-mental state examination; OR

=

odds ratio;

♂

=

men;

♀

=

women