SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

REVIEW

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 4 • NOVEMBER 2010

145

Limitations

Limitations of these studies include being restricted to special

populations like women,

16

women with osteoporosis

18

or nurses.

17

Another common limitation is the ascertainment of diabetes by self-

report

16,17,20

or even mailed self-report questionnaire.

19

The cognitive

assessment was sometimes performed by telephone,

17,19

which may

be less reliable than examinations by qualified or trained assessors.

One study introduced two additional cognitive tests during

follow-up (Digit Symbol Test and Trails B test) but the only test

used at baseline and follow-up (modified MMSe) did not generate

statistically significant data.

16

The utilisation of confounders varied

among the studies ranging from only a few confounders (age,

education, race and depression)

18

to a broad spectrum of covariates

(age, education and hormone use in women, baseline score, BMI,

hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, depression, smoking, alcohol

and physical activity).

19

Summary

Though there are many hints of a causal association between

diabetes and the development of cognitive decline, definitive proof

of a protective effect of antidiabetic treatment by controlled or

even randomised placebo-controlled studies is still required.

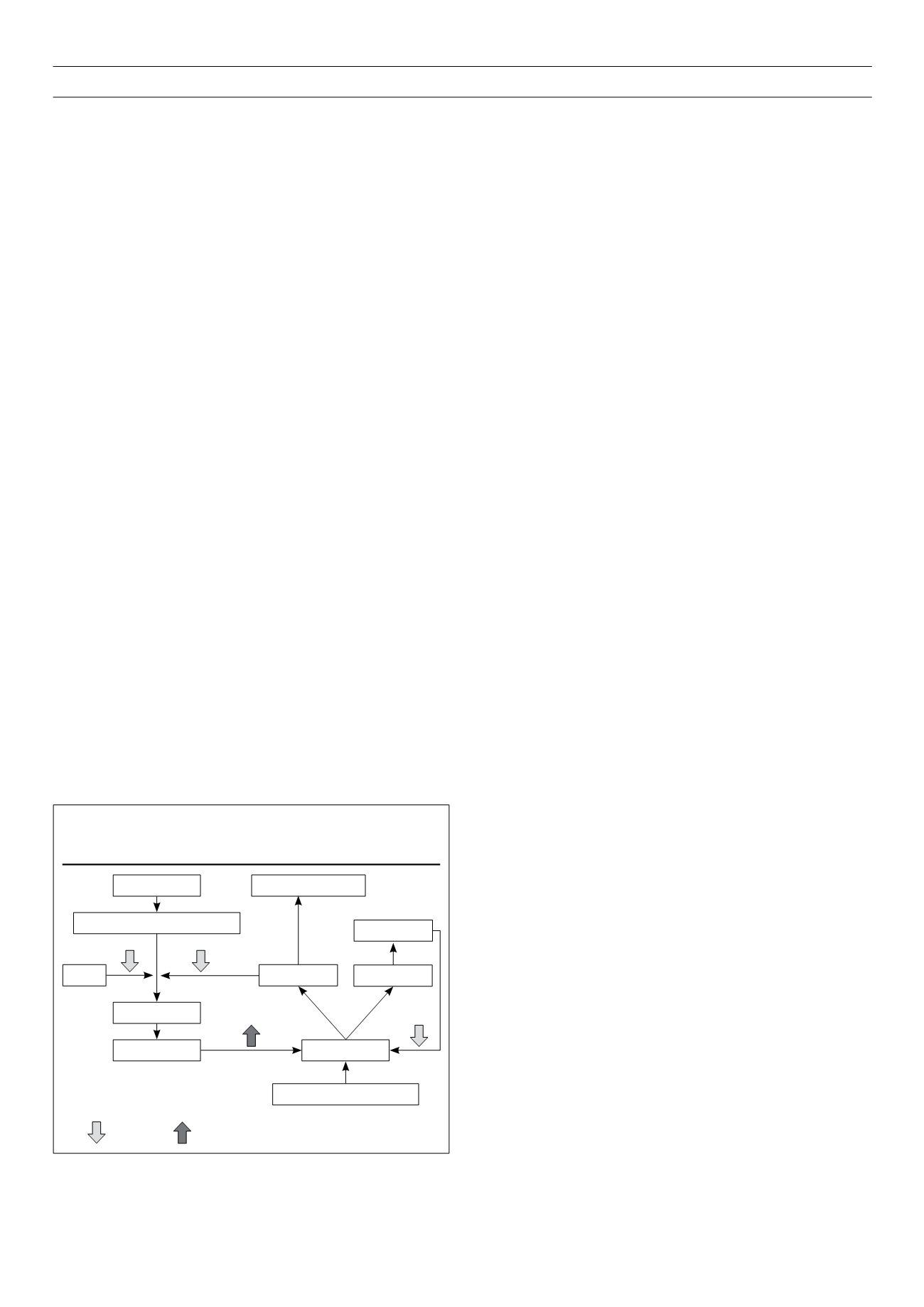

Hyperlipidaemia

Pathological and experimental data suggest that cholesterol

may play a role in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment and

dementia (Fig. 1).

23

A relationship between amyloid deposition and

serum hypercholesterolaemia in the human brain was detected

in autopsy cases of patients older than 40 years.

24

An association

between severe circle of Willis atherosclerosis and sporadic

dementia was found among 54 autopsy cases.

25

Studies on hyperlipidaemia and cognitve decline

The finnish CAIDe study evaluated the impact of midlife serum

cholesterol levels on the subsequent development of mild cognitive

impairment among 1 449 participants. After an average follow-up

of 21 years, a midlife elevated serum cholesterol level (

≥

6.5

mmol/l) was a significant risk factor for MCI (oR 1.9; 95% CI 1.2–

3.0) after adjustment for age and BMI.

26

In a retrospective cohort

study of 8 845 participants, aged 40–44 years, high cholesterol

was associated with a 40% (HR 1.42; 95% CI 1.22–1.66) increase

in risk of dementia after 30 years.

27

The french Three-City-Study, a

population-based cohort of 9 294 subjects, reported an increased

risk for subjects with hyperlipidaemia (OR 1.43; 95% CI 1.03–1.99)

independent of all major potential confounders.

28

In contrast to these trials, studies with participants of older age

couldnot confirmthis result of elevated cholesterol beinga risk factor.

In the Italian longitudinal Study on Aging with 2 963 participants

(age 65–84 years), serum total cholesterol had a borderline (non-

significant) trend for a protective effect.

29

A population-based

cohort study with 2 356 participants, aged 65 and older, found no

association between cholesterol and subsequent risk of dementia

after adjustment for several cofounders (age, sex, education,

baseline cognition, vascular comorbidities, BMI and lipid-lowering

agent use).

30

In a cross-sectional and prospective community-based

cohort study including 4 316 Medicare recipients, 65 years and

older, only a weak relationship between cholesterol levels and the

risk of vascular dementia was observed.

31

Several reasons could explain the paradoxical situation

that hypercholesterolaemia is apparently a risk factor in

midlife but becomes a more protective factor in older age.

Hypercholesterolaemia in the elderly may reflect a good dietary

status and overall health, whereas low levels of cholesterol could

be the result of poor nutrition caused by cognitive decline or other

medical problems.

32

Studies with statins

The majority of observational and prospective studies suggested

an association between statin use and cognitive decline, especially

Alzheimer’s dementia.

28,33,34

A population-based cohort study

comprising 1 674 older Mexican Americans with a five-year

follow-up found, after adjustment for several risk factors, that

statin users were about half as likely as non-statin users to develop

cognitive decline (HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.34– 0.80).

35

In the prospective

population-based Rotterdam Study with 6 992 participants and a

mean follow-up of nine years, statin use was associated with a

decreased risk of Alzheimer dementia (HR 0.57; 95%CI 0.37–0.90),

compared with no use of cholesterol-lowering drugs. There was no

difference between lipophilic (simvastatin, atorvastatin, cerivastatin)

or hydrophilic statins (pravastatin, fluvastatin, rosuvastatin), but

non-statin cholesterol-lowering drug use (fibrates, nicotinic acid,

etc.) was not effective.

36

On the other hand, two large placebo-controlled trials found no

positive association between statin therapy and cognitive decline.

The HPS reported no protective effect of simvastatin on cognitive

decline after five years among 20 536 high-risk vascular participants

aged between 40 and 80 years.

37

In the PRoSPeR trial, which

included 5 804 elderly high-risk vascular participants (aged 70–82

years), pravastatin had no significant effect on cognitive function.

38

A recent Cochrane review based on these two randomised trials

concluded that statins given in late life to individuals at risk of

vascular disease have no effect in preventing dementia.

39

Detailed

analyses of the latter study designs might explain the negative

results despite the large number of participants. Both studies

were not primarily designed to assess cognitive function. neither

included a baseline measurement of cognitive function, which

makes an accurate evaluation of any statin effect difficult.

40

The

Figure 1.

Simplified model of metabolic pathway of cholesterol and

amyloid

b

23

Key:

= inhibition,

= upregulation

Acetyle-CoA

3-HMG-3-Methyl-glutaryl-CoA

Statins

Mevalonat

Cholesterol

Tau phosphorylation

Sphingolipids

Amyloid

b

40 Amyloid

b

42

y-Secretase

Amyloid precursor protein