VOLUME 11 NUMBER 4 • NOVEMBER 2014

153

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

REVIEW

receiving intensive therapy had a significantly lower risk of CVD (HR

0.47, 95% CI 0.24–0.73), nephropathy (HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17–

0.87), retinopathy (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.21–0.86) and autonomic

neuropathy (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.18–0.79).

39

The mortality benefits

of such an intervention were also investigated in an extension

of the STENO-2 study (mean 13.3 years follow-up), where the

multifactorial intervention was shown to have a sustained benefit

on both vascular complications and cardiovascular mortality.

40

Y

et

al

though a comprehensive risk factor approach is essential when

treating patients with type 2 diabetes, data from the STENO-2

study show that despite reductions versus conventional treatment,

multifactorial interventionis insufficient to prevent the development

or progression of microvascular disease in up to 50% of patients

(Fig. 1). It is, therefore, clear that there is a need for renewed focus

on eff ective interventions that are capable of reducing the residual

risk of cardiovascular events and microvascular complications in

patients with type 2 diabetes receiving optimal therapy according

to current standards of care.

Quantifying cardiovascular risk

Patients with type 2 diabetes benefit from sustained and early

intervention for risk factor control; however, treatment interventions

are often initiated too late for maximum CVD benefit. Ensuring that

we are quantifying risk correctly is crucial to achieving early risk

factor control and addressing the residual cardiovascular risk seen

in type 2 diabetes patients.

The concept of medical intervention based on estimated total

CVD risk in asymptomatic patients is well established both in the

UK

41

and internationally.

42,43

Underpinning this are studies such as

the Framingham Heart Study, which to date has enrolled three

generations of participants to identify the common factors or

characteristics that contribute to CVD.

44

These data have enabled

researchers to construct multivariate risk prediction algorithms

intended to provide an estimate of CHD or CVD risk over a specified

time period, generally 10 years.

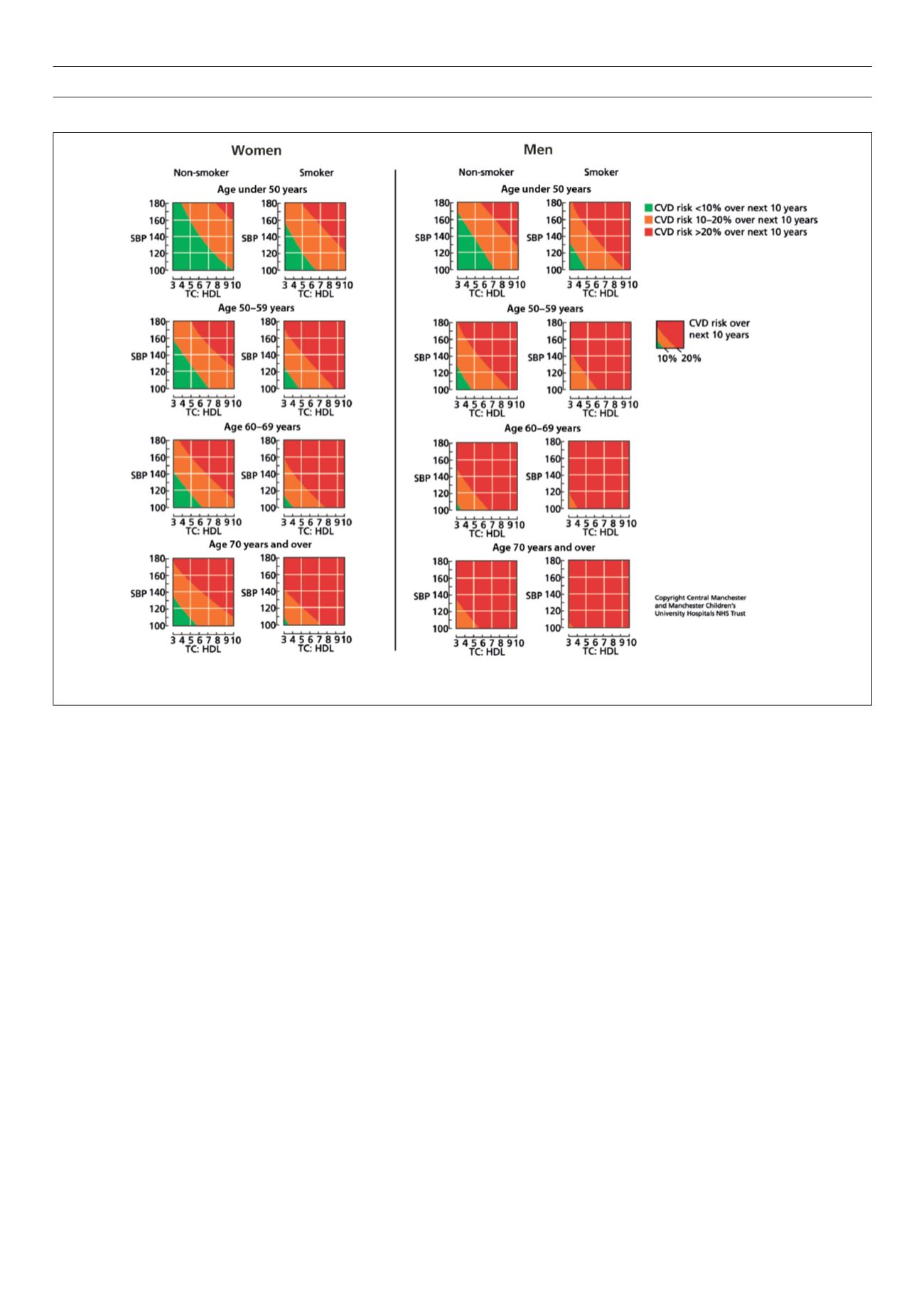

The second edition of the Joint British Societies’ guidelines on

cardiovascular disease in clinical practice (JBS-2) uses a risk estimate

tool adapted from the equations published from the Framingham

study in 1991.

45

The tool estimates total CVD risk (a combined

endpoint of CHD, stroke and transient cerebral ischaemia) for an

asymptomatic individual from several, wellestablished risk factors

such as age, sex, smoking habit, systolic blood pressure and ratio of

total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol.

This is then expressed as a probability of developing CVD over 10

years, based on the number of cardiovascular events expected over

10 years in 100 men or women with the same risk factors as the

individual being assessed. Charts have subsequently been created

to easily assess risk based on these factors (Fig. 2), and are split into

Reproduced from British Cardiac Society, British Hypertension Society, Diabetes UK, HEART UK, Primary Care Cardiovascular Society, Stroke Association. Joint BritishSocieties' guidelines on prevention of

cardiovascular disease in clinical practice.

Heart

2005;

91

(suppl 5). With permission from BMJ Publishing Group

Figure 2.

JBS2 CVD risk prediction charts for men and women.

41