154

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 4 • NOVEMBER 2014

REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

CVD risk categories of ≥ 10%, ≥ 20% and ≥ 30% over 10 years.

Asymptomatic individuals with a CVD risk of ≥ 20% are classified

as high risk, with this level being a threshold for treatment with

antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapies. It should be noted that

charts have not been created for patients with diabetes, and several

studies have suggested that these types of equations considerably

underestimate the risk of both cardiovascular disease and mortality

in this group.

46-48

Guidelines instead recommend all patients with

diabetes should be considered high risk and managed to the same

lifestyle and defined risk-factor targets as individuals with established

CVD and others at high 10-year risk of developing CVD.

41

However, there are well recognised limitations to a 10-year risk

metric for the calculation of cardiovascular risk. The 10-year risk

metric is dominated by two particular risk factors – chronological

age and gender. This fact effectively disenfranchises the middle-

aged and females, resulting in a delay in initiating treatment until a

particular chronological age is reached. Lloyd-Jones and colleagues

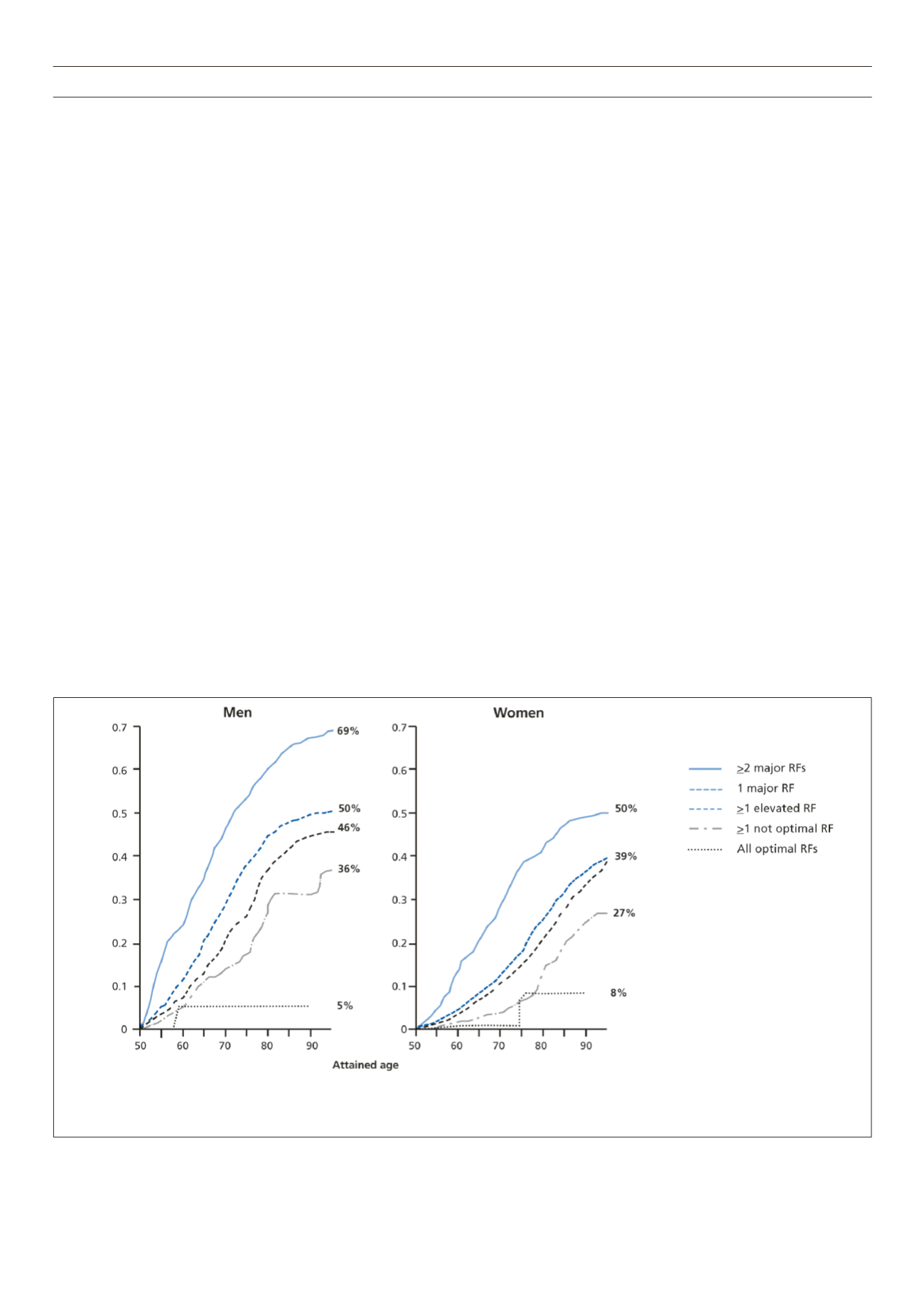

evaluated data from the Framingham Study to examine the lifetime

burden of CVD by traditional risk factor burden at 50 years of age.

Participants were stratified into five mutually exclusive categories,

as shown in Fig. 3, and they found that an absence of risk factors

at 50 years of age is associated with a very low lifetime risk for CVD

(5.2% for men and 8.2% for women). Conversely, those with two

or more major risk factors for CVD at 50 years of age had a markedly

higher lifetime risk (68.9% for men and 50.2% for women), and

for both men and women the adjusted cumulative incidence curves

across risk strata separated early from those without risk factors

and continued to diverge throughout the lifespan.

49

The importance of early risk-factor intervention is reinforced

by observational data from patients with a nonsense mutation in

the gene PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9),

resulting in lifelong reductions in LDL cholesterol. It was found

that in those with the mutation, a 28% lifetime reduction in mean

LDL cholesterol translated into an 88% reduction in the risk of

CHD (

p

= 0.08 for the reduction; HR: 0.11, 95% CI: 0.02–0.81).

50

Moreover, a recent meta-analysis of published data has estimated

the effect of long-term exposure to lower LDL cholesterol on the

risk of CHD mediated by nine poly-morphisms in six different genes.

Mendelian randomisation studies were combined in this meta-

analysis and showed that all nine polymorphisms were associated

with a highly consistent reduction in the risk of CHD per unit

lower LDL cholesterol with no evidence of heterogeneity of effect.

A meta-analysis combining non-overlapping data from 312 321

participants revealed that naturally random allocation to long-term

exposure to lower LDL cholesterol was associated with a 54.5%

reduction in the risk of CHD for each mmol lower LDL cholesterol.

This represents a three-fold greater reduction in the risk of CHD

per unit lower LDL cholesterol than that observed during treatment

with a statin started later in life.

51

It is clear, therefore, that the use of a 10-year risk metric

disenfranchises clinicians to control risk factors in younger patients

and treatment interventions are often initiated too late for maximum

CVD benefit. For this reason, the third edition of the Joint British

Societies guidelines (JBS3) is expected to advocate a move from

the current 10-year risk score to a lifetime CVD risk calculator. The

lifetime risk calculator will tell patients how likely they are to suffer

a cardiovascular event at various points in their lives.

It is likely that this move to assessing lifetime risk will result in

intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk at an earlier stage.

When should we intervene to reduce cardiovascular

risk?

In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that despite the

impressive gains made through the use of 10-year risk calculators,

Optimal risk factors are defined as total cholesterol < 4.65 mmol/l (< 180 mg/dl), blood pressure < 120/< 80 mmHg, non-smoker, and non-diabetic. Not optimal risk factors are defined as total cholesterol

of 4.65 to 5.15 mmol/l (180 to 199 mg/dl), systolic blood pressure of 120 to 139 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of 80 to 89 mmHg, non-smoker, and non-diabetic. Elevated risk factors are defined as

total cholesterol of 5.16 to 6.19 mmol/l (200 to 239 mg/dl), systolic blood pressure of 140 to 159 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of 90 to 99 mmHg, non-smoker, and non-diabetic. Major risk factors

are defined as total cholesterol ≥ 6.20 mmol/l (≥ 240 mg/dl), systolic blood pressure > 160 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure > 100 mmHg, smoker, and diabetic.

Figure 3.

Remaining lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease in men and women at 50 years of age

49