28

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 • MARCH 2014

REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

incretins and their interactions in glucose/energy homeostasis and

gut biology are still unclear.

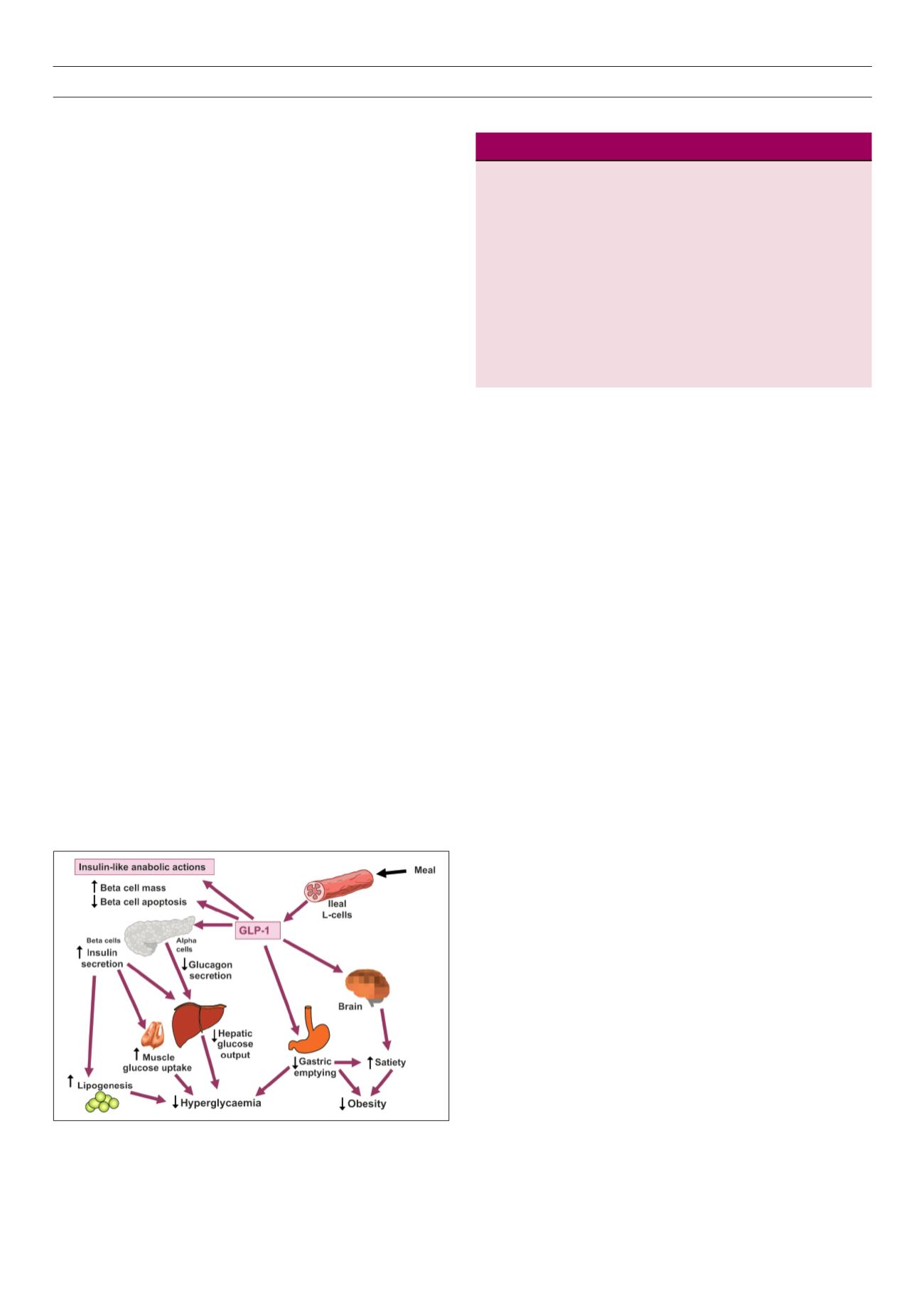

Incretin-based therapies are relatively new additions to the

management of type 2 diabetes (Fig. 2). They are either inhibitors

of the DPP-4 enzyme (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin and

linagliptin), which prolong the effect of endogenous GLP-1, or

analogues of GLP-1 (exenatide, liraglutide and lixisenatide) that are

resistant to the action of the DPP-4 enzyme. The inhibitors of DPP-4

generally reduce the enzyme’s activity in serum by 80%, which

causes a doubling of postprandial levels of biologically active native

GLP-1.

12,13

Compared with the sustained pharmacological increases

in the serum levels of GLP-1 analogues, DPP-4 inhibitors produce a

relatively modest and transient rise in postprandial GLP-1.

14

Hence,

the GLP-1 analogues are more efficacious in reducing body weight

and achieving glycaemic control.

As the insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 occurs only when plasma

glucose levels are raised, incretin-based therapies have a lower

propensity to cause hypoglycaemia. Incretin-based therapies have

rapidly become an established component of our armamentarium

for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Their main advantages are

the weight-losing/neutral properties and the relatively low risk of

hypoglycaemia.

The receptor for GLP-1 is expressed in a number of human tissues,

including the pancreas, intestine, lung, kidney, breast, brain, heart

and endothelium; and also in various endocrine tumours, especially

pheochromocytomas.

16

However, the receptor is thought to be

absent or sparsely expressed in human liver, spleen, lymph nodes

or adrenal gland.

16

Therefore, it is likely that the clinical effect of

endogenous GLP-1 and incretin-based drugs is not just confined to

glycaemic control mediated through insulin release, but could also

include actions on a diverse array of tissues that are implicated in

many physiological and pathological processes.

In this brief review article, we outline the main physiological

effects of GLP-1 (Table 1). We also hypothesise and explore novel

pharmacological effects of incretin-based therapies, based on the

known distribution of GLP-1 receptors, and provide a focus for

future research in this field.

Effects of GLP-1on blood pressure

In a series of large, randomised clinical trials termed LEAD

(Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes),

17

liraglutide produced

a modest but significant reduction (between 2 and 6 mmHg) in

systolic blood pressure, without any significant change in diastolic

blood pressure.

18–20

Subjects on liraglutide therapy also experienced

a significant reduction in their body weight, which might have

accounted for at least some of the change in blood pressure;

however, in one of the studies, the improvement in blood pressure

occurred before any substantial weight loss occurred, suggesting a

weight-independent mechanism by which GLP-1 influences blood

pressure.

21

A trend towards a significant reduction in systolic blood

pressure was also noted during exenatide treatment.

22

Experiments using rat models suggest that incretin-based

therapies lower blood pressure by modulating central and

peripheral neural pathways.

23

GLP-1 also seems to have diuretic and

natriuretic properties that may explain the anti-hypertensive effect.

24

Recent evidence from experiments on mice hearts demonstrates

the secretion of ANP following activation of the GLP-1 receptor in

the atrium.

25

Blood pressure may be regulated via the gut–heart

axis, in which GLP-1 and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) play a role.

Preclinical studies show favourable effects on endothelial function

in animals, for example: stimulation of nitric oxide production

and reduced production of adhesion molecules.

26,27

A recent meta-

analysis shows an increase in the heart rate of 1.86 (95% CI 0.85–

2.87) in patients treated with GLP-1 analogues. This increase was

more pronounced for long-acting drugs such as liraglutide and a

once-weekly preparation of exenatide.

28

The anti-hypertensive effect is confined to systolic blood

pressure and is variable in clinical trials. Therefore, GLP-1 analogues

should be currently regarded as a treatment for diabetes only, and

additional anti-hypertensives should be considered in patients with

raised blood pressure.

Effects of GLP-1 on the heart

In one clinical study, continuous GLP-1 infusion was given for 72

hours to 10 patients with an ejection fraction < 40%, following

an acute myocardial infarction and successful primary angioplasty.

When compared with 11 subjects treated with placebo, the GLP-1

treated patients had a significant improvement in left ventricular

ejection fraction, from 29 ± 2 to 39 ± 2% (

p

< 0.01). Interestingly,

this was noted in patients both with and without diabetes, and

independent of infarct location.

29

In a recent study, 172 patients

with myocardial infarction were randomised to receive exenatide

or placebo infusion for 6 hours, commencing 15 minutes prior to

primary angioplasty. The infarct size in relation to the area at risk

Figure 2.

Sites of action of GLP-1 to reduce hyperglycaemia and weight gain.

Source: reproduced with permission from

Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis

.15

Domain

Action of GLP-1 and GLP-1 based therapies

Vasculature

Modest improvement in systolic blood pressure.

No change in diastolic blood pressure.

18–20

Heart

Protective against ischaemic damage.

29

Possible improved prognosis in cardiac failure.

32

Brain

Enhanced satiety and reduced caloric intake.

34

Neuroprotection in animal models.

37,38

Kidneys

Enhanced sodium excretion.

43

Protection against diabetic nephropathy in animal

models.

45,46

Gastro-intestinal tract Reduced gastric motility.

47,48

Possible risk of

pancreatitis.

54–59

Thyroid

Medullary cancer in rodents. No effect in humans

67,68

Body composition

Reduced body fat mass

69,76

Table 1.

The effects of GLP-1 on major organ systems.